It is my great pleasure to introduce Bryana Joy to you. Her work as a visual artist and writer are a breath of inspiration and a cause for real rejoicing. And I am absolutely delighted to say that Bryana has also joined The Cultivating Project as a fellow team member! You will be seeing more her beautiful work in the months ahead right here at Cultivating and I couldn’t be more pleased!

LES: Bryana, what is the story behind naming your blog site “Having Decided to Stay”?

BJB: This question really gets straight to the heart of my life story, which has been a long chronicle of repeated relocation, travel, and exposure to a great many different cultures and ways of life. From the age of three, I grew up in Turkey, a Middle Eastern Muslim country with a rich cultural heritage and diverse population, although not without its own painful internal struggles. This complex and beautiful country was home to me throughout my entire childhood, so when my family moved back to the U.S. rather unexpectedly when I was about fifteen, the transition was excruciating. It was tumultuous time for all of us and I felt uprooted and floundering, without a sense of purpose.

It was during this time that I began to learn about the astonishing constructive power of joyous contentment in the midst of circumstances we can’t change. I discovered the backstory behind Jeremiah 29:11, the oft-quoted promise of “a hope and a future.” If you back up just a few verses, to Jeremiah 29:4, you find some startling context that really amplifies the significance of this familiar verse. You find God telling the exiled Israelites to thoroughly invest themselves in the country in which they are living as captives. “Build houses and live in them,” he says. “Plant gardens and eat their produce…Seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile, and pray to the Lord on its behalf.” He tells them they are going to be in Babylon for seventy years. [Seventy years! That’s a whole lifetime.] And then, only after all that, does he say, “I will come to you and fulfill my good promise to bring you back to this place. For I know the plans I have for you,” declares the Lord, “plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.”

These words really spoke to me at that spot in my life and I began to make a conscious effort to do my best to love people well in the place where I was and not to squander my time wishing I was somewhere else. I began to write poems in real earnest, many of them exploring the new ideas I was working to embody, and the poems from this period are collected in my first book of poetry, which I titled Having Decided To Stay. I was living with my family on a farm in East Texas at that time, and so gardening imagery was a big part of my creative expression. The title poem in my book ends with this resolution:

I intend to make them my people who people

this unwhole place, to be of them, to be an

outsider no longer, to no longer stand aloof.

No Pygmalion spent more time chiseling on knees

than I intend to do. I intend to embrace the soil

of this place, to clear the air with true stories and a

wholesale slaughter of lies; to garden so immaculately

that everyone will talk about our roses.

I intend to love you here also

as I have loved you in every other place.

These poems, these declarations, were what held me together throughout the darkest chapter of my life thus far and so the current title of my blog site is a nod to that.

LES: Would you give us some background to why courage is such a vital issue to you and how does that tie in to the Good, True, and Beautiful?

BJB: Well, in all honesty, I think one of the biggest reasons I find myself continuously coming back to the concept of courage is because it’s become an absolutely vital part of my daily life. I have some trauma in my past that still resurfaces in the form of severe anxiety and so I know firsthand that fear can be physically, morally, and emotionally debilitating. What I love about the word “courage” is that it doesn’t mean being the kind of person who is not easily scared. If it did, I couldn’t qualify. But no, it means the ability to do something that does scare us. And since I often feel terribly small and inadequate, and since there are so many, many things that scare me, cultivating and developing courage within myself is a consistent and essential need.

So how do we get courage? What does that look like in the real world? For me, courage is about perspective and imagination, and this is where the Good, True and Beautiful comes into play. When my surroundings are mundane and colorless and the world around me shrinks to the tyranny of the minute, it’s hard to have courage. It’s hard to face hardships when I don’t have confidence in the meaning of my work and my breath, when I’ve lost sight of the great and glorious story of which I am a part. So the way I get courage is by steeping myself in things that remind me of the wideness of the world and the illimitable goodness of God. And my hope is that my work will provide a space for others to do just that.

LES: Tolkien. It is abundantly self-evident that Tolkien is a tremendous influence in your work. Tell us a bit about how you first encountered him and what is it in his work that inspires yours.

BJB: Ah, Tolkien. Where to begin? I first read The Lord of the Rings with my younger sister when I was twelve and thirteen years old and it has thoroughly permeated and enriched my world. To this day, a line of his writing or a strain of music from Howard Shore’s soundtrack, or a Silmarillion painting from Ted Nasmith has the power to bring me back to the happiest years of my childhood. I think that at first what I loved was the sheer wonder of the story and the way it opened doors on a world unlike and apart from this one – a fairytale of cosmic proportions. The Lord of the Rings told of a bigger world than the one around us and my sister and I wanted to incorporate that world into every area of our own. We played the movie soundtracks day and night and read and reread the books. We crafted costumes and wore them unashamedly. At 6:00 AM on cold mornings we slipped out to the woods alone to walk among graceful, imaginary elves and ambush orcs.

But as I grew older, my love for Tolkien’s homemade mythology grew into something deeper and more grounded. I started to love Middle-Earth not because it was set apart from and better than the world I lived in. I started to love it because it is the world I live in. I think the gift Tolkien has given us in The Lord of the Rings (and perhaps a gift that all great literature gives us in one form or another) is the gift of clarified vision. He has created a world in which, to a great extent, things really do look like what they are on the inside. Middle-Earth gives us glimpses of a place where the realest things are visible. The orcs and goblins are hideous and aggressive and deformed, stained with the Red Eye and the White Hand, symbols of their slavery. The elves are comely and full of tangible grace, with silver in their hair and starlight in their homes. In our world, it isn’t like that. Our eyes can’t always pierce through the physical to see things in the way that God sees them. But if we could, I think we would do a great many things very differently. And how much courage we would have!

For example, like many people, I sometimes find prayer a lonely and discouraging pursuit. Sometimes it feels like I am pouring out the very center of my soul to God and he isn’t so much as glancing in my direction. I can, of course, and should, build up my faith with scriptures like Psalm 145:18, which declares that “the Lord is near to all who call on him, to all who call on him in truth.” If I’m being real, though, there are times when all the words and verses in the world seem to ring hollow. However, there is an image that has met me, on occasion, and carried me home: Arwen, kneeling on the bank at the Ford of Bruinen and speaking terrified but faithful words of power over the water. And the water, turning into foaming white horses and sweeping all her enemies away. Sometimes what I need more than anything else is a story to spark my imagination and remind me of the reality that I can’t see. I need to be reminded to speak prayers with Arwen’s confidence, assured of my position as a child of the Most High God and without a doubt in my mind that the foaming horses are just around the corner, even though I can’t see them and might not recognize them if I did.

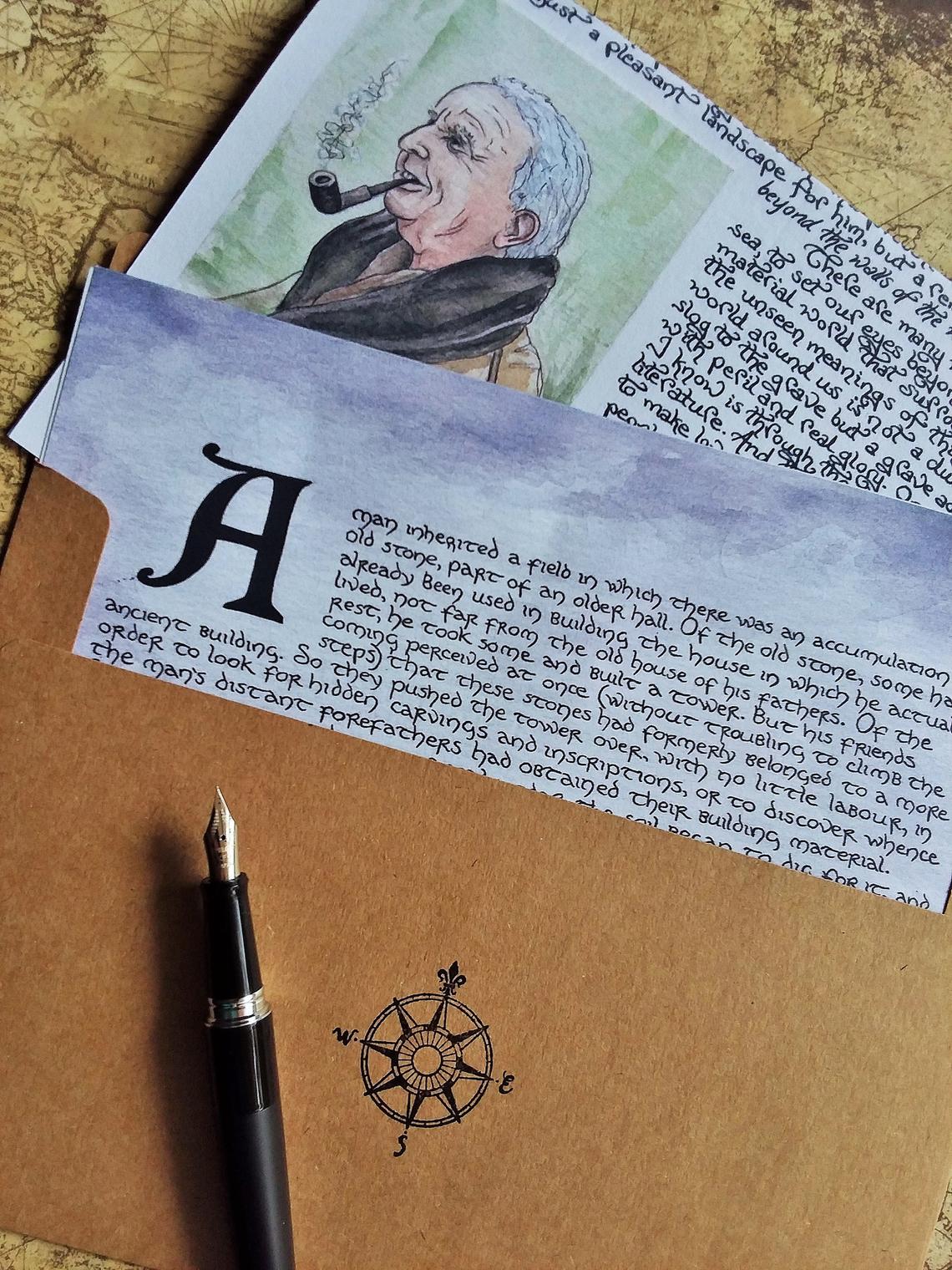

LES: One of the most remarkable acts of art that I’ve seen in a decade is your Letters From the Sea Tower. Bryana, tell us about this marvelous endeavor. What inspired you to launch it? What ideas came to you first to create it? What is the purpose of it for your readers? What does it take to produce it? Where do you see it sailing out to?

BJB: Shortly after my seventeenth birthday, back in that stretch of time when I was learning how to practice contentment, I began filling up hundreds and hundreds of pages of illustrated prayer journals, documenting and painting the good things in my life. I kept a running gratitude list, inspired by Ann Voskamp, and wrote lengthy and polished reflections and descriptions of nature and the world. I peppered each page with quotes and poems and hymns I found in my readings. Creating this curated collection of beauty and truth brought me tremendous satisfaction and helped me to hold onto my joy in those bleak years.

As I grew older, I stopped keeping these elaborate journals because I wanted to use my time creating work I could freely share with others. But I never grew out of my attachment to this form of artistic expression. I have always been drawn to the practice of capturing snippets of my time on the planet using both words and watercolors, of connecting splendid and courage-giving thoughts and ideas with paintings of the world around me. And I think this is really the first original root of the Letters From The Sea Tower.  Back in the summer of 2018, I went out one day to check the mailbox. I threw away an armload of advertisements and coupons and brought in a rather hefty pile of bank statements and bills. And I got hit by a wistful memory of the joy of mailtime that I experienced as a child when I had friends with whom I exchanged occasional letters. In that moment, something clicked in my mind and I thought, “what if I could bring that back for people?” I sat down and began hastily typing up a sheet of ideas and questions, feeling a tad bit foolish but allowing myself to dream for at least a little while.

Back in the summer of 2018, I went out one day to check the mailbox. I threw away an armload of advertisements and coupons and brought in a rather hefty pile of bank statements and bills. And I got hit by a wistful memory of the joy of mailtime that I experienced as a child when I had friends with whom I exchanged occasional letters. In that moment, something clicked in my mind and I thought, “what if I could bring that back for people?” I sat down and began hastily typing up a sheet of ideas and questions, feeling a tad bit foolish but allowing myself to dream for at least a little while.

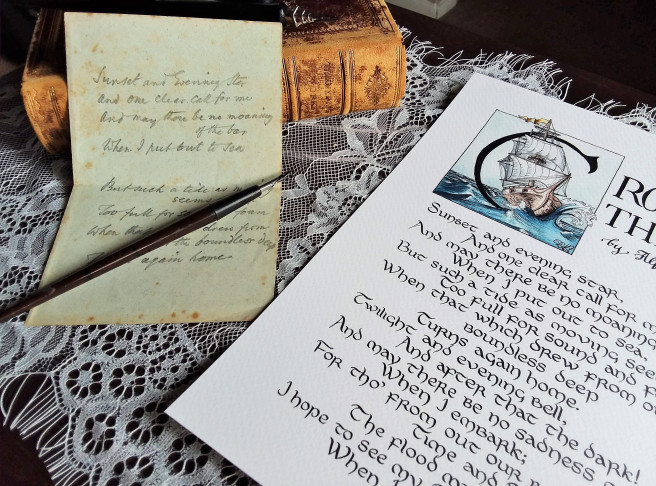

It didn’t take me too long to figure out what form I wanted the letters to take. My two great creative passions are literature and art and I already had a hobby Etsy shop where I sold prints and original paintings of illustrated calligraphy quotes. I knew I wanted to write about literature in a way that made it relevant and fascinating for everyone. I knew I wanted to illustrate the letters with watercolor sketches and paintings. I knew I wanted people to open their mailboxes and be awed by the beauty of the envelopes. Most of all, I knew I wanted to give people courage in a tangible form they could hold in their hands or carry in their pockets or hang up in their homes.

To my knowledge, there are only a handful of other artists who offer letter subscriptions and most of these are travel-oriented. So as far as I can tell, my idea of creating literature-based letters is a complete novelty. Thus, explaining it to others was a bit of a challenge and I could tell most people didn’t really understood what I had in mind. I went through a period of uncertainty as to whether there would be enough interest to cover the substantial costs associated with launching a project of this size, but my dear sister gave my confidence a huge boost when I first told her about the project over the phone and this assurance from her helped me to push through and take the risk.

The process of creating the letters is quite involved because it’s very important to me that every component is of the highest quality. Since beauty is one of the main elements of my work, every detail matters. The first step in producing the letters is creating the text and paintings. I typically begin researching the material for my letter the month before, taking notes and making sketches as I go. Then, towards the end of that month, I type up the letter text, a process that typically takes me about five hours. After that, I begin planning my layout; deciding where to put the illustrations and calculating how much space I’ll need to reserve for the handwritten letter. It’s astonishing how many hours of work can be ruined by just one small mistake. One unfortunate drop of ink, accidentally-overlooked word, or smear of paint can be catastrophic. So I work very slowly and methodically. The whole thing takes me about a forty-hour work week. At the end of it, I scan my creation and color-correct the digital copy for printing. I print the letters in my own home, on 32 lb 100% cotton paper.

The quality of the paper is really important to me because it has a huge effect on the color and feel of the printed letters and I really want each letter to be a gorgeous work of art in its own right. This is also why I mail the letters in big A9 envelopes, even though they are more expensive. An A9 envelope allows me to fold the page just one time, minimizing creases and making the letters more suitable for framing or display.

After printing the letters, I personalize each one by hand with the recipient’s name and the packaging date and location. I also hand-write all the addresses on the envelopes and use ink stamps to embellish each envelope. I get a lot of comments about the vintage postage stamps on the letters. Yes, they are real unused postage stamps from olden days and yes, at present, that is how I pay for all the postage. I purchase these stamps in bulk from various collectors and then combine different values to arrive at the required postage amount. This part of the process is pretty time-consuming but it gives each letter its own colorful collection of historical flair and I’m pretty attached to it.

So far, the response to the letters has been extremely enthusiastic. I’ve been receiving messages almost every day from people telling me how much their letters mean to them and I want to make this experience available to as many people as I possibly can. In January, I quit my job in order to take on the letters as a full-time commitment. In February, I sent out 115 letters and used over 900 stamps. As you can probably imagine, printing, personalizing, and packaging this many letters can be a bit daunting. But I really believe in the value of this project and I absolutely love what I do. I’d very much like to see the Letters From the Sea Tower continue to grow and I’ve already begun taking some steps to streamline my process a little more so that I can accommodate a much bigger subscriber base.

LES: Why does Garrison Keillor’s statement that ‘the meaning of poetry is to give courage’ speak so resonantly to you? How does this connect to your phrase “the war from where we are?”

BJB: Poetry has been big part of my life since I was a child. I was homeschooled by a dedicated mother who was a student and practitioner of the ideals and principles of the 19th century British educator Charlotte Mason. Our home was full of books and full of literature. I and my siblings began memorizing, copying, and reciting classic poetry at a young age and I never really got it out of my system. I grew up on Beowulf, Shakespeare, Alfred Lord Tennyson, William Wordsworth, Emily Dickinson, A. E. Housman, Christina Rossetti, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Robert Frost, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and G.K. Chesterton’s “The Ballad of the White Horse.” These lyrics shaped my language and my writing.

As a teenager, I won several thousand dollars in international poetry contests, and this gave me the impetus to take the craft of poetry very seriously. In my college and young adult years, I fell in love with Gerard Manley Hopkins’ vivid, gemlike verse and W.S. Merwin’s “The Rain in the Trees.” I dabbled in Robert Browning and W.B. Yeats and delved into W.H. Auden. I discovered e.e. cummings. I read Jane Kenyon and Mary Oliver and was absolutely captivated by a lecture on “The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock.” I attended a poetry reading by Tyehimba Jess.

I also took two semesters of poetry workshops under the brilliant and generous Dr. Robert A. Fink, and one of the primary lessons I took away from his classes is that good poetry springs from attentive and patient examination of the world around us. What does that have to do with courage, you might ask? Well, poetry is a distillation of life. The task of a poet is to examine an incident or an idea with painstaking attention and retell it in such a way as to extract the essence of it, the significance, the meaning. That’s what poetry is: it’s a presentation of meaning. And meaning is the key to courage. If our lives have meaning, if what we do matters, we will have courage, because we can’t afford not to. This is what Garrison Keillor is talking about when he says “the meaning of poetry is to give courage.”

Several years ago, I wrote a blog post titled, “The War From Where We Are,” which later became an entire category on my blog. The idea behind this phrase is that we are all caught up in a great war, whether or not we wish to be. If you are alive, you are a character in the story of the world. You will be beset by dangers and temptations and you will have opportunities to make glorious choices. As Auden says, “you will see rare beasts and have unique adventures.”

The catch is that we don’t get to see our stories from the outside. And at some point, every great epic of faithful heroism in literature and history, from Abraham to Samwise Gamgee, looked very dismal from the inside. As I wrote in my blog post, “a hero’s own story is never clear to him.” And I think this inability to see the whole story is the biggest challenge to our courage. If we could see what the story was and we had confidence that we were playing an important role, if we knew we were going down in the Hall of Faith like Mary or Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego, wouldn’t that lift our chins a little and put a spring in our step? But as it is, clouded as our vision is, muddled as our paths seem, how easy it is to lose heart.

So to my mind, this is where the meaning-making power of poetry comes in. Good poetry–even extremely specific poetry about someone else’s birthing experience or childhood memories or career as a mechanic–affirms meaning. That’s its whole purpose. And that affirmation of meaning gives us courage because it prompts us to see the meaning in our own situation.

LES: Your blog post titled “On Ringbearing & Abiding & 2013” is one I think ought to be required reading for every Cultivator. I am haunted by your phrase “But the only words that really matter are the ones we really live.” You wrote that six years ago. Much has changed in your life since then. How do you see that now? Is that a bigger, fuller truth for you than when you first wrote it?

BJB: Oh my. This is a big question. Yes, my life has changed enormously over the past six years. As you’ve probably noticed, I haven’t written very many new blog posts in the past few years. Part of the reason for that is because I was a full-time college student until May of 2018 and I simply didn’t have time to write blog posts, which usually take me several hours of hard, focused work. When I went to college, I stepped away from most of my online platforms because I had a flood of new opportunities to invest in face-to-face friendships and I wanted to take advantage of these.

But there are other reasons too. The past four years have been a challenging time of shattering and reconstruction in my inner life. The love of God has been shattering some of my false confidence and arrogance and prejudices. My values and my ways of seeing things have gone through some intense restructuring and it has been unbearably painful at times. I am reminded of C.S. Lewis’ analogy in Mere Christianity:

“Imagine yourself as a living house. God comes in to rebuild that house. At first, perhaps, you can understand what He is doing. He is getting the drains right and stopping the leaks in the roof and so on; you knew that those jobs needed doing and so you are not surprised. But presently He starts knocking the house about in a way that hurts abominably and does not seem to make any sense. What on earth is He up to? The explanation is that He is building quite a different house from the one you thought of – throwing out a new wing here, putting on an extra floor there, running up towers, making courtyards. You thought you were being made into a decent little cottage: but He is building a palace. He intends to come and live in it Himself.”

I don’t think I’m even close to becoming the palace the Almighty intends. But after all this, I better have lost a wall or two and acquired at least a new wing!

One thing is for sure: in this time away from writing, living well has become a far higher priority to me than any amount of writing. When I composed that phrase back in the day, I remember being very anxious about hypocrisy. I enjoyed writing and was pretty good at it and had time to do it, so I wrote a great deal. But even back then, I knew I was young and untried in so many things and I was sometimes a little concerned by how deeply I cared about my writing. I knew that craft and creation can become obsessions that distract us from our reason for doing them in the first place. In fact, I wrote about this on another occasion as well, exploring what Auden calls “the treason of all clerks” in his poem, “At The Grave of Henry James”:

All will be judged. Master of nuance and scruple,

Pray for me and for all writers, living or dead;

Because there are many whose works

Are in better taste than their lives, because there is no end

To the vanity of our calling, make intercession

For the treason of all clerks.

It’s odd to look back on this now, because I strongly remember feeling sad and unimportant after writing about it. But although I still believe it’s crucial for every writer and artist to revisit these ideas regularly, I think my long break from writing (outside of assignments and research papers) has helped me plant my feet firmly in the real world. In the in-between time, I’ve built many friendships and met and married a very good man. These things keep me grounded and I suspect my writing will be grittier and more honest because of them.

LES: How does the merging of visual art and literature reflect the values you have learned from your faith?

BJB: In the Bible, we read that faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen. (Hebrews 11:1) I think this familiar verse has profound implications for the roles of art and imagination within the family of God. Our faith has its roots in the proposition that there is an unseen world around us and in us, that if we could strip off the limitations of space and time and physicality, we would be awed by the breadth of the story we are in and the meaning underneath everything.

This is why I believe imagination is a crucial skill for Christian people to cultivate and practice. We need to practice broadening our vision and breaking the hold of the tedious immediate. We need to create and inhabit good stories that remind us who we want to be in our own world’s story. In his wonderful book, Telling The Truth: The Gospel as Tragedy, Comedy, and Fairy-Tale, Frederick Buechner says, “The power of stories is that they are telling us that life adds up somehow, that life itself is like a story.” And if anyone has a reason to believe that, it’s Christians.

But it isn’t always easy to believe. Sometimes it feels like our lives are riddled with completely useless tragedies that brought no good to anyone. Sometimes we’re exhausted by the press of needs around us and the feeling that all our effort is going nowhere and leading to nothing. Sometimes we’re simply numbed by the monotony of living and the heap of minor disappointments that have piled up around us like a walled fortress. For times like this, we need the eyes of imagination. We need imagination to see beyond the boundaries of time and space, to see what an epic story God might be writing, to imagine how our circumstances might be a part of it.

For me, merging visual art and text/literature is an important part of sparking imagination, both in myself and in others. Obviously, (even if we judge solely by the length of this interview!) I love words. I love the craft of stringing them together to plant beautiful and challenging ideas in other people’s minds and hearts. Artful, lucid writing gives me goosebumps, usually accompanied by a strong desire to share the glory with others. And I’ve found that sometimes the best way to do that is to incorporate illustration. Words are powerful, but truly receiving them requires us to do some mental and emotional work. Sometimes paintings can be the spark that sets the tinder burning; because images captivate us and draw us in faster than text can hope to do. I see my illustrations as little windows into the possible, little snapshots from my imagination. I want to remind people that their own imagination can be every bit as powerful and potent. And no matter how high our imagination climbs, it can never be better than what is actually ahead. We cannot out-imagine God. That’s in the Bible. 1 Corinthians 2:9 says:

no eye has seen, nor ear heard,

nor the heart of man imagined,

what God has prepared for those who love Him.

LES: Bryana, you and your husband are planning a move to England for a year this coming September. Many Cultivating readers will have a wistful sense of longing to go with you in some way, being that we are a tribe of Anglophiles and British Lit Lovers. How is that circumstance coming to pass and what do you hope to emerge from that time in England?

BJB: Yes, it’s true. My husband Alex has accepted an offer to study for an M.A. in Victorian Literature and Culture at the University of York so we plan to spend a year living in this historic city in Northern England. This really is a dream for both of us as our connections to the UK are deep-seated and longstanding. Growing up, I had extended family living in Wales and I spent some happy times on a sheep-farm in the high green hills. In college, Alex and I took a class on Celtic Christianity and had the opportunity to spend two absolutely wonderful weeks in Ireland on a trip organized by the talented and gracious Kiran Wimberley, a Presbyterian minister and musician who also creates gorgeous Celtic renditions of the Psalms. As a child, the first history book I remember reading was H.E. Marshall’s Our Island Story and I grew up living geographically closer to the UK than to the US. Honestly, I’ve always felt a closer connection to British history and culture than to anything here in the States and almost all my favorite writers and authors are British, so it feels really natural to be heading across the pond at this point in our lives.

While Alex is studying there, I plan to continue creating and mailing the Letters From the Sea Tower and will certainly share paintings and stories from our travels. Although I haven’t yet determined exactly how postage will work when we move, it’s very possible that, for a time at least, the letters may be arriving with British postage stamps!

I also plan to take advantage of the opportunity to spend an extended period of time in the country that shaped so many of the writers I admire. Alex and I have a long list of literary sites we’re hoping to visit and although I know we won’t get to all of them, I do have my heart set on a trip to the Lake Country and a visit to Hill Top Farm.

Additionally, I hope to take some space and time to focus on polishing and publishing some more poetry. I have written quite a bit of poetry over the past year and I have more in the works, but poetry is a huge time investment for me and it can be difficult to make it happen when there are so many other things pressing for my attention. Although I have no concrete plans towards this end yet, I will say that I’ve been playing with the idea of pursuing an M.F.A. in poetry at some point in the future and I’d love to someday offer workshops to help others grow as writers and thoughtful observers of the world. These are just a few things I’m casually dreaming about right now, but whether they do or don’t come to pass, I’m tremendously grateful for this chance to spend time pursuing my art in one of my favorite places in the world.

Additionally, I hope to take some space and time to focus on polishing and publishing some more poetry. I have written quite a bit of poetry over the past year and I have more in the works, but poetry is a huge time investment for me and it can be difficult to make it happen when there are so many other things pressing for my attention. Although I have no concrete plans towards this end yet, I will say that I’ve been playing with the idea of pursuing an M.F.A. in poetry at some point in the future and I’d love to someday offer workshops to help others grow as writers and thoughtful observers of the world. These are just a few things I’m casually dreaming about right now, but whether they do or don’t come to pass, I’m tremendously grateful for this chance to spend time pursuing my art in one of my favorite places in the world.

Looking back on my life, it seems to me that so much of it has been about waiting and hoping and fumbling through the darkness with the (sometimes very fragile) conviction that good things were ahead. But right now I feel like I’ve finally stepped out of a murky forest into a clearing where the House of Tom Bombadil is sitting in tranquility, full of honey and cream and candles. I am doing the work I love on a full-time basis and I find it truly fulfilling and joyous. I’m also celebrating nine months of being married to a really good man, a man kinder and more supportive than I thought possible. Our lives are not free from trouble, but we are happy.

In her novel, Gilead, Marilynne Robinson’s protagonist says something I wrote down in my commonplace book years ago and which has been with me ever since: “Now that I look back, it seems to me that in all that deep darkness a miracle was preparing. So I am right to remember it as a blessed time, and myself as waiting in confidence, even if I had no idea what I was waiting for.”

I drew courage from this quote for many years. I even wrote a poem about it. And I’d like to conclude by sharing that poem here, because I know that some people reading this today might be in one of those dark places of waiting and I’d like to tell them, “hold on. You’re not alone.”

In the end, every one of us alive in this poor old, broken world is waiting for something. And it will be worth it.

IN CONFIDENCE

“What is real about us all is that each of us is waiting.”

(–W.H. Auden, A Christmas Oratorio)

for the clean sun the clean rain

the big wave and the grey-eyed hurricane

for the children to come home

we have put supper on

it will not be long now

for red over the great hills

the big fish with the gold scales and thirsty gills

for the blue river to arrive

out of the high mountains

it will not be long

for the white star, the white horse

and whatever is at the end of course

for the little lacy flowers to open

for the wet butterfly-tongues

not long now

for the trumpets of the trains

the big sky smoky-white with aeroplanes

we will jump high laughing

waving our small hands so fast

not long

for whatever is coming

with big slow footsteps and soft humming

to get here wearing just

whatever it has on hand

will be perfect

we who have been hanging, hanging

on the noises in the darkness

will not hang back we will

run forward with our arms wide

calling welcome welcome

The beautiful featured image above is by the marvelous photographer Aaron Burden, whose work we always appreciate and admire. You can find Aaron’s generously shared images on Unsplash here.

Lancia E. Smith is an author, photographer, business owner, and publisher. She is the founder and publisher of Cultivating Oaks Press, LLC, and the Executive Director of The Cultivating Project, the fellowship who create content for Cultivating Magazine. She has been honoured to serve in executive management, church leadership, school boards, and Art & Faith organizations over 35 years.

Now empty nesters, Lancia & her husband Peter make their home in the Black Forest of Colorado, keeping company with 200 Ponderosa Pine trees, a herd of mule deer, an ever expanding library, and two beautiful black cats. Lancia loves land reclamation, website and print design, beautiful typography, road trips, being read aloud to by Peter, and cherishes the works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and George MacDonald. She lives with daily wonder of the mercies of the Triune God and constant gratitude for the beloved company of Cultivators.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

Add a comment

0 Comments