Scholar Diana Glyer is fascinated by collaboration. Her life’s work has been studying the Inklings, particularly the ways they collaborated with and influenced one another. In Bandersnatch: C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and the Creative Collaboration of the Inklings, she makes her decades of research accessible to lay readers—an especial gift to writers and other creative types.

Glyer’s focus in Bandersnatch is two-fold: the Inklings’ collaboration and what we can learn from it about the nature of collaboration and creativity. The book, as one might expect, is chock full of Inkling anecdotes, many of them amusing, most of them rich with implications for our own writing lives. In particular, the stories here help to defuse the myth of the lone genius and encourage writers, often an introverted and solitary breed, to reach out and “simply connect”—to ask for feedback, offer encouragement, and become “writers in community.”

For me the term “writers in community,” especially in conjunction with the Inklings, conjures images of Oxford pubs and Old World college rooms with men in tweed coats shuffling through piles of handwritten pages and uttering words of wit and erudition, while pipe smoke swirls about in the air. My life doesn’t look like that. At all. Turns out the Inklings’ writing community didn’t look like that most of the time, either. Throughout Bandersnatch, Glyer makes clear that writing in community is elastic and flexible. It doesn’t look just one way. Even for the Inklings, it looked different at different times, depending on who was part of the group and what projects they were working on.

This reality became clear to me in my most recent reading of Bandersnatch. Again and again I was struck by the inequality of the Inklings’ relationships. They all gave and received feedback, but they didn’t all give feedback on every piece of everyone else’s work, nor did they all receive feedback from every other Inkling on each piece that they wrote. For instance, when Lewis was writing The Problem of Pain, Robert Havard, a medical doctor and fellow Inkling, was actively interested in the topic, contributed “a great deal…to the unfolding draft,” and gave Lewis copious and detailed comments. Later, when Havard wrote the appendix for the book, Lewis returned the favor by carefully revising it. But this exchange of feedback was not commensurate—Havard gave far more feedback than he received, for The Problem of Pain is more than twenty times longer than his appendix.

This sort of thing happened repeatedly, where one Inkling would be more invested in another Inkling’s project than any of the others were, or would be more invested in a certain stage of the project. Tolkien, for instance, seems to have been better at promoting Lewis and his books than helpfully critiquing them.

As a writer, I found this give-and-take reassuring, for I have often felt guilty that I do not have many reciprocal writing relationships, as if that somehow reflected badly on me not just as a writer but as a person.

Recognizing that the Inklings often had projects that only a few of the others were interested in, or that some were better at certain kinds of feedback than others, has helped me relax and realize that lack of reciprocity is normal, and it’s fine.

I was also deeply encouraged by the section on failed projects in Chapter 6, “Mystical Caboodle.” (The chapter titles are one of the many delights of the book.) In the past I have tended to beat myself up for not finishing things I start (and they are legion), but reading about the Inklings’ unfinished projects suddenly helped me see my own “failed” projects as part of the creative process. Even great writers like Lewis and Tolkien started projects that they never finished. Sometimes good ideas simply don’t come to fruition. The timing isn’t right or external interest isn’t sufficient to justify publication or the writer’s interest in it fizzles. Whatever the reason, failed projects are simply part of what it means to be a writer.

It wasn’t only the failed projects that I found so encouraging; it was also the projects that took decades to finish. Lewis wanted “to write a masque or play based on the Cupid and Psyche myth” back in 1922. He fiddled with it, turned it into a poem, and then dropped it for almost 30 years before turning it into his novel Till We Have Faces. For those 30 years, that project probably felt like a failure. But it wasn’t. It was just percolating. And how glad I am that it did. It’s my favorite of his novels, and I realize that much of its richness is because he let it stew for so long and waited till he was a good enough writer to do justice to the story he wanted to tell. I imagine the story he wanted to tell changed a good deal over the years, too, and is also the richer for having been set aside for so long. I find this very hopeful. What seems like a failed project may simply be one we aren’t yet ready to write.

And that is why we need community with other writers.

Alone, we are prone to forget and to despair. Together, we remind one another that failure is part of the process, and it’s not fatal.

We encourage one another to keep going, or to rest a bit, when the mountain of words seems too big to climb. And we celebrate with one another when we finally make it to the top. Sometimes we give the feedback or the encouragement. Sometimes we receive it. But whether we give or receive, we are helping one another become better writers—because, as Bandersnatch so vividly shows, creativity flourishes in community.

In a way, the book itself is a kind of community. It reads like it’s written by a wise writing mentor, someone who points out signposts along the way, offers gentle course corrections, and reminds you that others have trod this road. You can follow in their footsteps, she says, and here’s how.

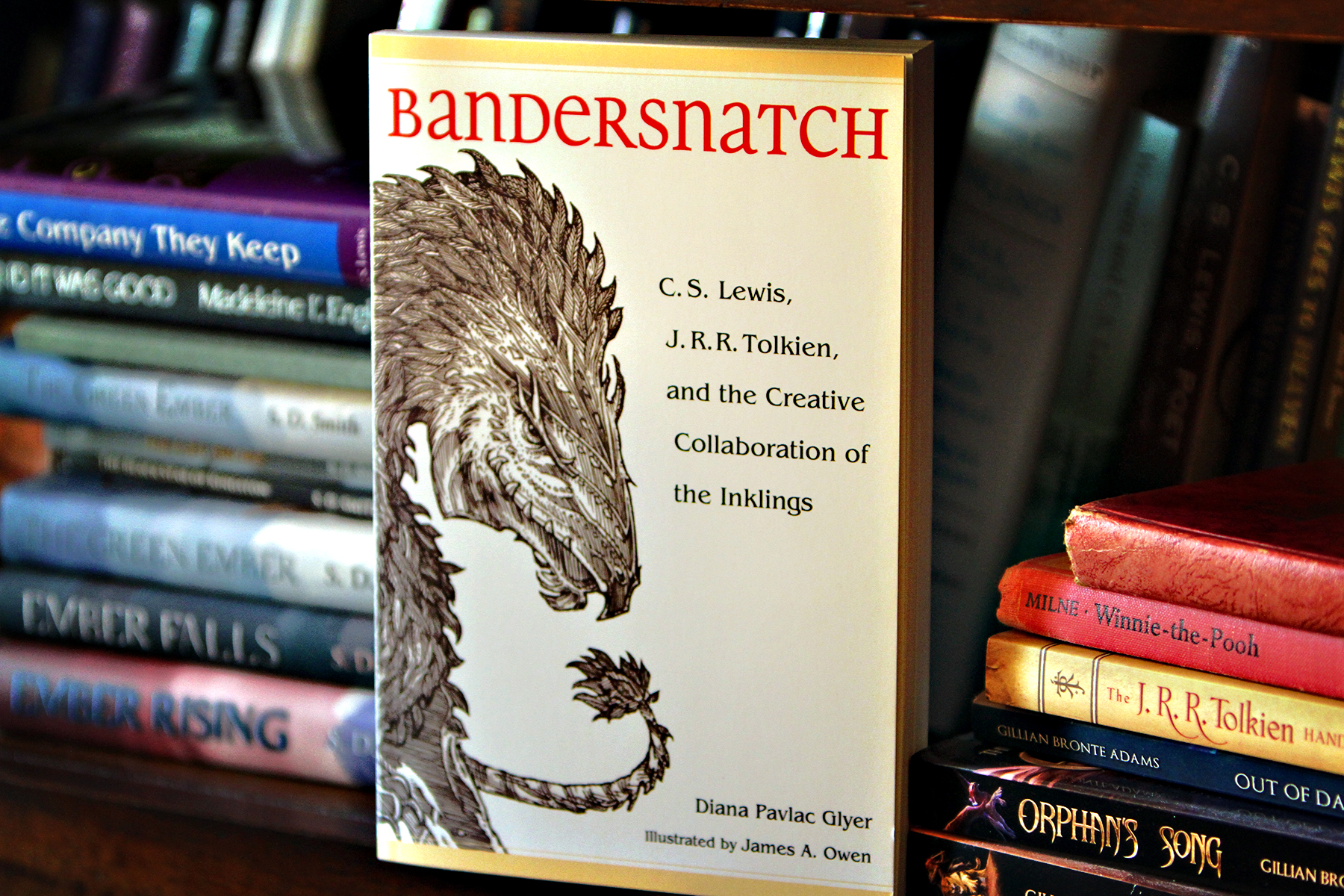

The featured image is (c) Lancia E. Smith and used with glad permission for The Cultivating Project. It was made in the working office out of which Cultivating is created and published. It is an especially cherished volume. Diana Glyer is an inspiration and model of creative excellence for The Cultivating Project and all who know her.

K. C. Ireton is a multi-published author of both fiction and nonfiction books, including The Circle of Seasons: Meeting God in the Church Year and A Yellow Wood and Other Stories. She and her daughter, Jane, co-host Lantern Hill, a podcast for people who love books, children, and God. Visit kcireton.com to learn more about her work and download the first two chapters of her most recent book. Or visit her on Substack at kcireton.substack.com, where she publishes stories and liturgies.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

Thank you so much for sharing your thoughts on Bandersnatch. I have had the book sitting on my shelf for a little while now, and this has encouraged me to push it to the top of my t0-read pile.

Gillian, I’m honored I could provide the needed nudge to move Bandersnatch closer to the top of your list. Enjoy!