Malcom Guite is no stranger to readers of Cultivating. His books have illuminated our reading lives for years and we have been enchanted with his lectures, speaking events, and his Spell in the Library series on YouTube. In every venue, Malcolm Guite gives wisdom and insight into the intersections of faith, poetry, and imagination with an unflagging generosity. Cultivating has been blessed to run a series of remarkable interviews with Dr Guite over a 10 year period, and it our absolute delight to share this one with you all. Happy reading, friends, and a very Merry Christmastide to you all!

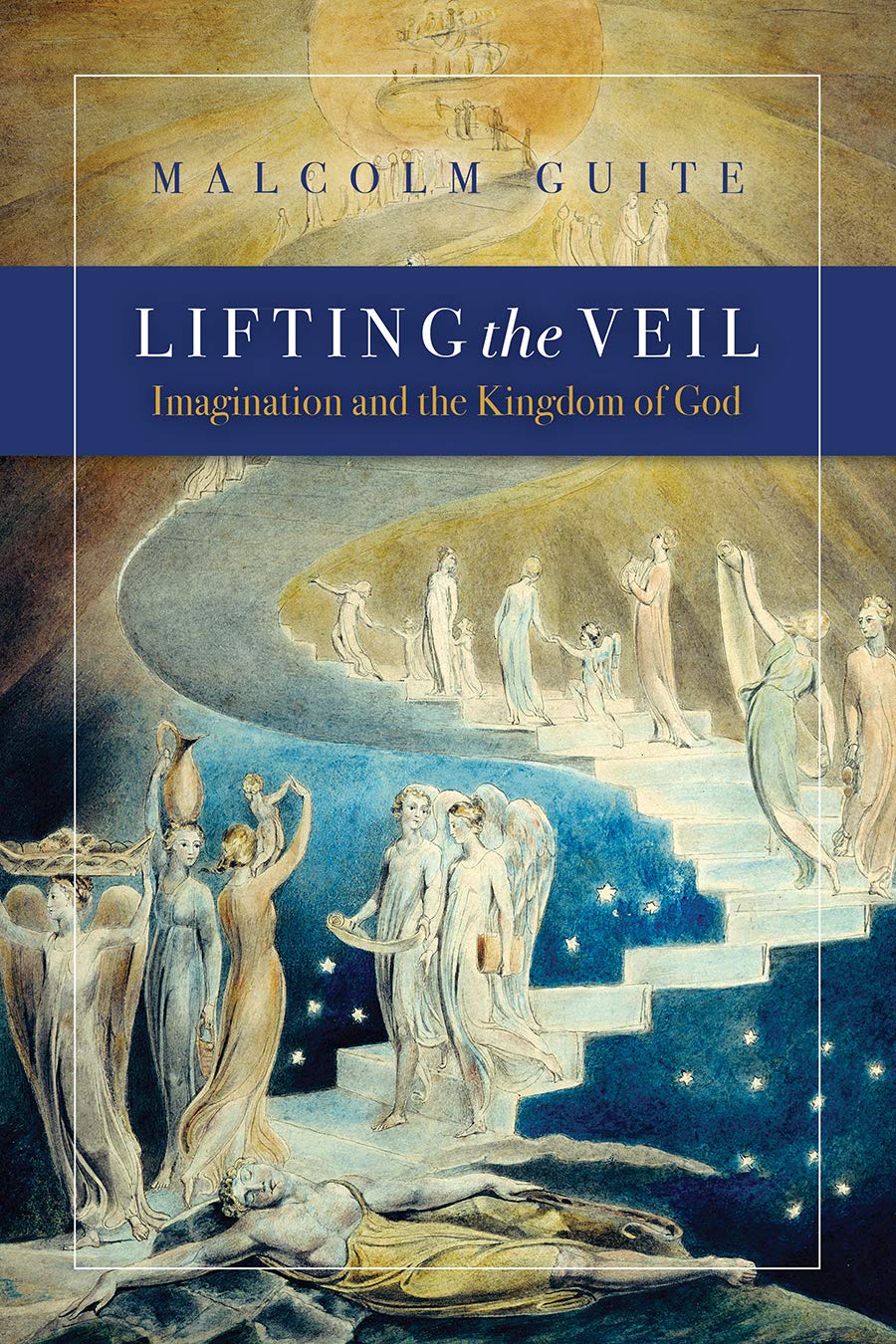

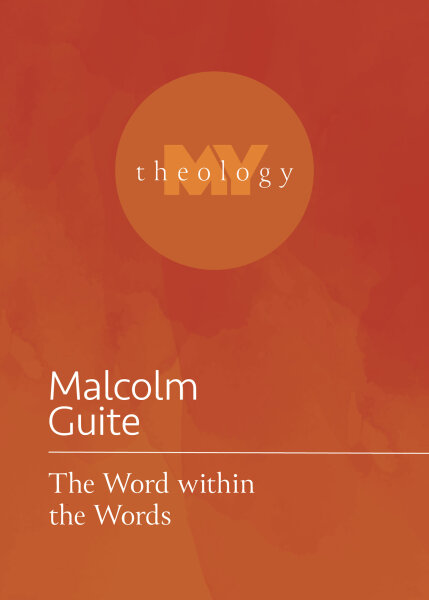

LES: Malcolm, you’ve recently published two new works through two different publishers. Lifting the Veil: Imagination and Kingdom of God came out this fall from Square Halo Books, and MY Theology: The Word within the words has been published by Darton, Longman Todd in the UK. It is coming out in the U.S. through Fortress Press (U.S.) and will be available January 18, 2022. The content for Lifting the Veil is based on your original series of lectures “Imagining the Kingdom” given for the renowned Laing Lectures Series at Regent College, Vancouver 2019. This is the first time you have worked with Square Halo as a publisher. How did this connection and decision to publish these lectures come about? How has your experience with them been different than other publishers you have worked with over the years?

MG: I’d come across a few Square Halo books and thought they were beautifully produced, and I met Ned Bustard from Square Halo at the Glen West workshop. He invited me to contribute to a book they were producing called The Lost Tales of Galahad, an invitation which had the happy effect of getting me started on my own longer, and long-postponed Arthurian project, so when I realized that I could and should turn the Laing Lectures into a book and wanted a North American publisher, Square Halo just seemed like the right choice.

LES: In the opening of Lifting the Veil, you write that this book is a “defense of the imagination as a truth-bearing faculty and more than that it is an appeal … to kindle our imaginations for Christ…” As a defense, this has been a long maintained one. You’ve written deeply about this defense (and a “redress”) in your superb book Faith, Hope, and Poetry. These books (F, H, & P and Veil) seem to be tied to each other, this latest one being a kind of echo of the earlier. And there are threads in this, of course, from Mariner, your biography of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Each approach is bearing witness to one core truth but though different written lens so to speak. Did working through the themes for Lifting the Veil show you something fresh to what you already know concerning imagination as a truth-bearing faculty? Did writing refine the way you see the work of imagination?

MG: Yes, there’s a deliberate link. I’d worked through the ideas and ‘set out my stall’ on Imagination in FH&P, but of course that was in some respects a specialized academic book. I had very much admired the way both Michael Ward and Diana Glyer, two serious scholars whose work I value had both taken their major academic monographs and re-worked/re-written them in more accessible form for a wider audience, Ward writing The Narnia Code from his Planet Narnia and Glyer producing the excellent Bandersnatch to make her findings in The Company They Keep more widely available. I was particularly impressed with the way Glyer reshaped her work so that it appealed particularly to young writers eager to learn from the example of the Inklings, and I thought I could take some of the insights from FH&P and draw out from them something that would be accessible and inspiring to young ‘creatives’ who were looking for some theological underpinning for their work and some encouragement from the poets of the past. So, in a way, Lifting the Veil is my Bandersnatch!

Having said that I have also introduced quite a lot of new material and engaged with poets I didn’t get to include in FH&P, including William Blake and RS Thomas, so I hope there will be something new and some further developments of my thought in Lifting the Veil for readers who already know FH&P.

LES: The idea of imagination as a truth-bearing faculty was nodded to by C.S. Lewis when he wrote, “For me, reason is the natural organ of truth; but imagination is the organ of meaning. Imagination, producing new metaphors or revivifying old, is not the cause of truth, but its condition.” How do we make the distinction between truth itself and meaning?

MG: I think Lewis’s famous distinction is very helpful. It is not either/or but Both And! Even the driest fact arrived at by science has to be grasped with and through the imagination if we are to see its significance and its place in the larger pattern, and of course the great scientists often make their breakthroughs with a leap of the imagination, what Einstein called ‘a thought experiment’ and Lewis called a ‘supposal’.

But I think I would join with Tolkien in going a bit further than Lewis was willing to go on this. Lewis says Imagination is ‘not the cause of truth’, but in fact it sometimes is. Both because all being, everything about which anything true can be said, springs into existence out of the imagination of God, but also because we are made in God’s image, we are, as Tolkien says, ‘sub creators’, and our sub creations, secondary worlds springing entirely from the imagination are in fact full of all kinds of truth. So, in that sense Imagination can actually be the cause of truth as well as the organ of meaning.

![]()

“…reality is itself numinous, translucent with glimmerings of the “supernatural,”

of something holy shining through.”

![]()

LES: One of my favourite lines in Lifting the Veil is this: “…reality is itself numinous, translucent with glimmerings of the “supernatural,” of something holy shining through.” You are writing this in context of Wordsworth and Coleridge using the arts to awaken the mind’s attention, or what we might call the ‘mind’s eye’. But this statement has traces of influence from MacDonald, Lewis, and Chesterton also. It reminds me of Lewis’s reference to the Bright Shadow that he saw while reading Phantastes and how after that reading, he experienced it washing over his everyday reality, and Chesterton’s comment, “The world will never starve for want of wonders; but only for want of wonder.” What do you do in your own life that allows you to keep open to wonder? Is this something that happens without intention or is it something practiced? Where do you have a sense of the numinous overlapping into ‘ordinary’ space and time?

MG: I think this openness to and experience of Wonder is both an unmerited gift of grace, and also, paradoxically a practice that can be cultivated. Although the experience of wonder often comes upon us suddenly, unbidden, and is experienced as sheer gift, we can nevertheless put ourselves in the way of it and be ready and open for it when it comes. We can go for long walks in the countryside with open eyes and ears, we can keep company with children and learn from their almost constant wonder and awareness, we can remember and be in touch with our own experiences of wonder as a child and be open to them again. And of course, one can read the poetry, view the art, and hear the music which will lift the veil and renew a sense of wonder in all our perceptions.

![]()

“All great art is a bridge with one foot in the world of comprehension,

the visible, the earth, and one in the realm of apprehension, the invisible, heaven.”

Malcolm Guite

![]()

LES: We live in a world of daily dualities. Day and Night. Right and wrong. Good and evil. Truth and falsehood. Life and death. The blessing and the curse. Earth and heaven. The invisible and the visible. The now and the not yet. Modern trains of thought try to make an indistinction of these defined realities and make ambiguous what is, and always has been, sharply distinct. The role of the artist is a calling, however, to reconcile the distinctions, and to integrate them not into ambiguity but into something greater – to give the invisible ‘a shape, a name, a local habitation’ – making visible what has been unseen. The great capacity of the imagination is its power to make a bridge between what we comprehend and what we apprehend; to integrate the dualities we live with and to make a home among them for us. Has the weakening of our collective imagination as Christians since the Enlightenment period influenced or fueled the contemporary deconstructionist movement? Is there a way to regenerate a wider movement to reclaim our imaginative faculties as believers even as we rekindle our imaginations individually?

MG: Yes. I think our capacity to perceive imaginatively has been marginalized for so long since the Enlightenment that it has begun to atrophy, and it needs to be regenerated. I think that in God’s providence the Inklings were raised up in the mid twentieth century to show us where we had gone wrong and to give a practical demonstration of what a regenerate, baptized imagination might look like and how it might see the world. The secular literary establishment, which was entirely committed to what Charles Taylor called ‘the immanent frame’ was of course threatened by them and tried to ignore them or dismiss them as irrelevant fantasists, but the great mass of the people knew better and bought their books in the millions, even voting for Tolkien as ‘the author of the twentieth century.

LES: Throughout the wide range of your work, including significant references in both Lifting the Veil and in The Word within the words, you bear testimony to the role that imagination has in facilitating living faith. How do you describe the intersection of imagination as a faculty of the mind with the life of the soul and spirit? How does imagination feed and support our living faith?

MG: That’s a very interesting question. We distinguish between mind, soul, and spirit, but we should not divide them, just as we distinguish between the persons of the Trinity but do not divide the substance. So, the mind’s active imagination feeds the soul and the soul’s innate capacity to intuit truth and love it before it even has an image for it is in turn informed and furnished by the imagination with images to body forth its apprehensions. The spirit, which communes with the Spirit of God, which searches all things is able to suffuse both mind and soul and is that power which baptizes the imagination.

We live in a world of images and our faith cannot be a living faith unless it, too, lives in the world of images enjoying them in themselves but always seeking God through them.

LES: Both Lifting the Veil: Imagination and Kingdom of God and My Theology: The Word within the words are deeply concentrated documents of a whole message you have been delivering throughout all your writing life. They are examples of the circle of telling being distilled and refined into increasingly smaller circles of essence and mastery. You are intimately familiar with this message as you spend your life serving this work. As a writer, does perfecting the language to give this truth “a local habitation and a name”, distilling it into a smaller and smaller frame become easier, or more demanding? Does the process change you?

MG: Yes, these were both exercises in distillation, and that is a very helpful discipline for a writer, and especially for a writer like me. I am never at a loss for words. On the contrary my danger is that I use too many and weaken what I have to say. This is why I have chosen the sonnet form, because it forces me to concentrate and distil what I have to say. It’s a challenge of course to do it well but I hope that the process of distillation in both these books has produced a stronger and more lasting spirit!

![]()

“My vocation as a poet attunes me particularly to the mysteries and beauties of language:

the magic of words, the cadences and music of sound but most of all, kindling and glimmering

through the words we use, the mystery of meaning itself and the wonderful vehicle of metaphor

whereby one thing can be transfigured by the meaning of another.”

![]()

LES: The Word within the words is a contribution to a series called My Theology. With this contribution you have been invited to give a formal statement expressing the core of your own theology as a poet and writer. The paradox to this is, of course, that true theology cannot be just one person’s theology. While it is, and must be, personal to be transformative, true theology exists beyond any single individual and stands in the integrity of its own life. We are given faith as a gift by grace. Our response of receiving that gift and living into it is in effect our gift back to our Maker. The study of God – theology – is how we grow to know Him better and be transformed in faith through that knowing. You have said regarding this book that what you are offering through it is a “Religio Poetae – the Faith of a Poet.” You see and know the holy Maker God through the lens of a poet’s eye. You know experientially God as Logos through your calling to words. How has that calling aided you in making peace with what you are not made to be? Because your vocation is to be one who calls words into visibility, how has the embodying of your vocation transfigured you?

MG: Gosh, that’s a big question! I think we all have to learn that vocation is both a calling to do some particular thing for God and therefore also a calling not to do many other things. But this is difficult to learn and still more difficult to put into practice because of course we are also all called to love and serve one another, and everyone can always find lots of uses for our time and lay obligations upon us. So, it takes real discernment to know which requests we should refuse with as good a grace as possible. I still struggle with this, and as a result, I get exhausted, and my primary work suffers. However, I always know when I am doing the primary thing, which is to kindle my own and other people’s imaginations for Christ, and when I am doing that, when it is actually happening on the page in front of me, then I am always exhilarated and energized.

![]()

“O Sapientia

I cannot think unless I have been thought,

Nor can I speak unless I have been spoken;

I cannot teach except as I am taught,

Or break the bread except as I am broken.

O Mind behind the mind through which I seek,

O Light within the light by which I see,

O Word beneath the words with which I speak,

O founding, unfound Wisdom, finding me,

O sounding Song whose depth is sounding me,

O Memory of time, reminding me,

My Ground of Being, always grounding me,

My Maker’s bounding line, defining me:

Come, hidden Wisdom, come with all you bring,

Come to me now, disguised as everything.” [1]

LES: I have gone back to your poem, O Sapientia, written in response to great antiphon “Sapientia” many times. Of all the pieces of poetry I have ever read, it anchors me most constantly in the numinous reality of God’s goodness and vastness. I hear the cadences of truth – the truths that were spoken by God as Logos, and brought all things into being, including me – and I am recentered. So much struggle and anxiety is stilled here when I read it. Do you ever go back to your own writing and find it speaking back to you in its own living voice as though it did not come from you but is answering you from beyond boundary lines of your own self?

MG: Yes. It’s a curious experience going back to your own writing, especially if it’s been a while since you wrote it. The best thing that can happen is that you read it with a kind of surprise, with a sense of discovery, as though someone else had written it. You have no ego invested in it anymore, it just exists as a work in its own right and you would be just as glad of it and just as pleased with it if someone else had written it. The My Theology book was in a sense an exercise in doing just that. The brief was to draw out from one’s own work the underlying themes and motifs that might cohere together in a consistent theological underpinning, something I had already done in other books for the work of other poets, for example in my work on Coleridge, only this time the poems were by some newcomer called Guite! So, I learned quite a lot from that and was relieved and pleased to see that there were consistent themes and there really was a developing theology, a great deal of it embedded or implicit in that very poem O Sapientia, which is the first poem I cite in the book and was in fact the first poem I wrote in what became my first full poetry collection, Sounding The Seasons.

I hesitated for some time before accepting the commission for the My Theology book because I was afraid that in drawing out a distinct theology from these poems I might be limiting or foreclosing on the many possibilities of meaning that each poem might hold for people, and I wouldn’t want to do that. I think each poem, if it is a poem at all, must be bigger on the inside than the outside. It must be continuously generative and suggestive of new meanings for each new reader and on each subsequent reading. So, whilst I hope what I offer in the My Theology book is true and helpful I would never want to suggest that it is in any sense definitive in its reading of my work. It is just one particular reading.

LES: These two books make fine companions to each other. Are there other books you would recommend they keep company with to expand conversation they offer?

MG: Well, I think the My Theology book can be read for comparison and contrast with some of the other books in the series. It is a very short book, as are the others, so that can be easily done. I think Alistair McGrath’s book in this series, when it comes out, might make an interesting companion to mine. I think Lifting the Veil could serve either as an intro to FH&P or possibly as a postscript. Someone who had read FH&P and asked themselves. ‘Now where do I go with this in my own life as an artist?’ might well find Lifting the Veil helpful.

![]()

LES: Writing these two books in such a close time frame to each other surely must have been exhausting. While writing them you also had major life events happening, too. As a rule, we seem to be given few ideal conditions or seasons for writing. This fact inevitably makes me think of Lewis’s comment in his essay “Learning in War-Time”,

“There are always plenty of rivals to our work… If we let ourselves, we shall always be waiting for some distraction or other to end before we can really get down to our work. The only people who achieve much are those who want knowledge so badly that they seek it while the conditions are still unfavourable. Favourable conditions never come.”

In this same essay (written to young scholars wondering about the value of continuing an education while the clamours of war were close at hand) Lewis offers three mental exercises which may serve as defenses against the three enemies that war-time conditions raise up against the scholar. I believe the conditions he is referencing are not fundamentally different for writers in this time, particularly Christians who write. Do you have mental exercises that you use to help you “soldier on” when working conditions are ‘unfavorable?” Do you find that observing those has a carry-over effect into deepening your practices of faith in other areas of life?

MG: Lewis is right. Conditions are never perfect and often not even favourable, so you just have to get on with it! But if you discipline yourself to put in the time it’s amazing what consequent graces arise. And then there are the silver linings in otherwise dark clouds. Covid Lockdowns for example really enabled me to work on my David’s Crown book and get that done, though they presented other problems. Likewise, there was space for these two books partly because I was not travelling to events but rather doing them from home by zoom. The other thing that helps me frankly is deadlines! Someone said that all you need to make art is something to say and not enough time. If you can endlessly postpone you will, but if someone else is counting on you, you get it done. This is true in our life of faith and our moral life as well, which is why we have church, why we can’t just be Christians on our own. We need community and commitment to draw out the best in us. Having said that, we need some solitude too. I am feeling frustrated at the moment because I really want to get on with my Arthuriad, and after a big burst of writing in the summer, I haven’t been able to turn to it for months.

![]()

“The poet is not content with a flimsy ‘imaginary’ insubstantial or merely wordy realm, but strives constantly to body things forth.

To show us real flesh and blood, to make of the poem a visible, approachable, local habitation in which we can at last,

see the invisible and give a name to those loves and apprehensions which give life meaning.”

![]()

LES: Incarnation. It means to embody. To make flesh. As in all things, our God has gone before us in this. He made into flesh and substance what had not been flesh. He made visible what had been invisible. Everything we are and every labour that goes into this world, is made possible only because we are ourselves incarnated and made flesh. Made in the image and likeness of our Maker, we are made to make. Made to enflesh. When you are writing, Malcolm, do you sense the Logos writing with you and through you, bringing to light that which has been invisible and unspoken?

MG: You are right to point to Incarnation as the key to Imaginative art and I discovered, when I was writing ‘The Word within the words’ that my theology is essentially and incarnational theology of the Logos, the Word made flesh. I think there is a logos with in each of us which is both the particular word with which the great Logos speaks us into being, for we are all little logoi, words from the Word. But I think there is also a sense in which the Logos, Christ Himself is also present and at work in us, as He promised He would be when we abide in Him, and He abides in us. When I am actually writing, in the full flow of composition, I am not really conscious of myself at all, but only of the words themselves, and I experience their flow and their arrangement as a gift, and often as a surprise, so in that sense I do feel that another is writing with me, that the Logos who is the kindled meaning of all things is kindling the words I use in me and for me and through me, kindling them not only for me, but also for others.

![]()

[1] Waiting on the Word: Malcolm Guite: Canterbury Press 2015: pp66

Featured image of Malcolm Guite is courtesy of Lancia E. Smith and used with her permission for Cultivating.

Lancia E. Smith is an author, photographer, business owner, and publisher. She is the founder and publisher of Cultivating Oaks Press, LLC, and the Executive Director of The Cultivating Project, the fellowship who create content for Cultivating Magazine. She has been honoured to serve in executive management, church leadership, school boards, and Art & Faith organizations over 35 years.

Now empty nesters, Lancia & her husband Peter make their home in the Black Forest of Colorado, keeping company with 200 Ponderosa Pine trees, a herd of mule deer, an ever expanding library, and two beautiful black cats. Lancia loves land reclamation, website and print design, beautiful typography, road trips, being read aloud to by Peter, and cherishes the works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and George MacDonald. She lives with daily wonder of the mercies of the Triune God and constant gratitude for the beloved company of Cultivators.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

Thank you so much for this interview. It is refreshing and encouraging. I especially appreciate the reminder that “Conditions are never perfect and often not even favourable, so you just have to get on with it! “

Holly, thank you kindly. I am so glad you this interview with Malcolm is an encouragement to you! I, too, have taken serious note of that warning from Lewis that conditions never are perfect, and often not even favourable. We must get on with our work even in poor conditions, including weary and imperfect hearts. We bring the obedience, The Lord brings brings the yield.