I believe that books find us when we are ready for them. This has been my experience too many times to chock it up to coincidence. This was the case with Walking On Water: Reflections On Faith And Art, when it found me in my early days of stepping into my own writing life.

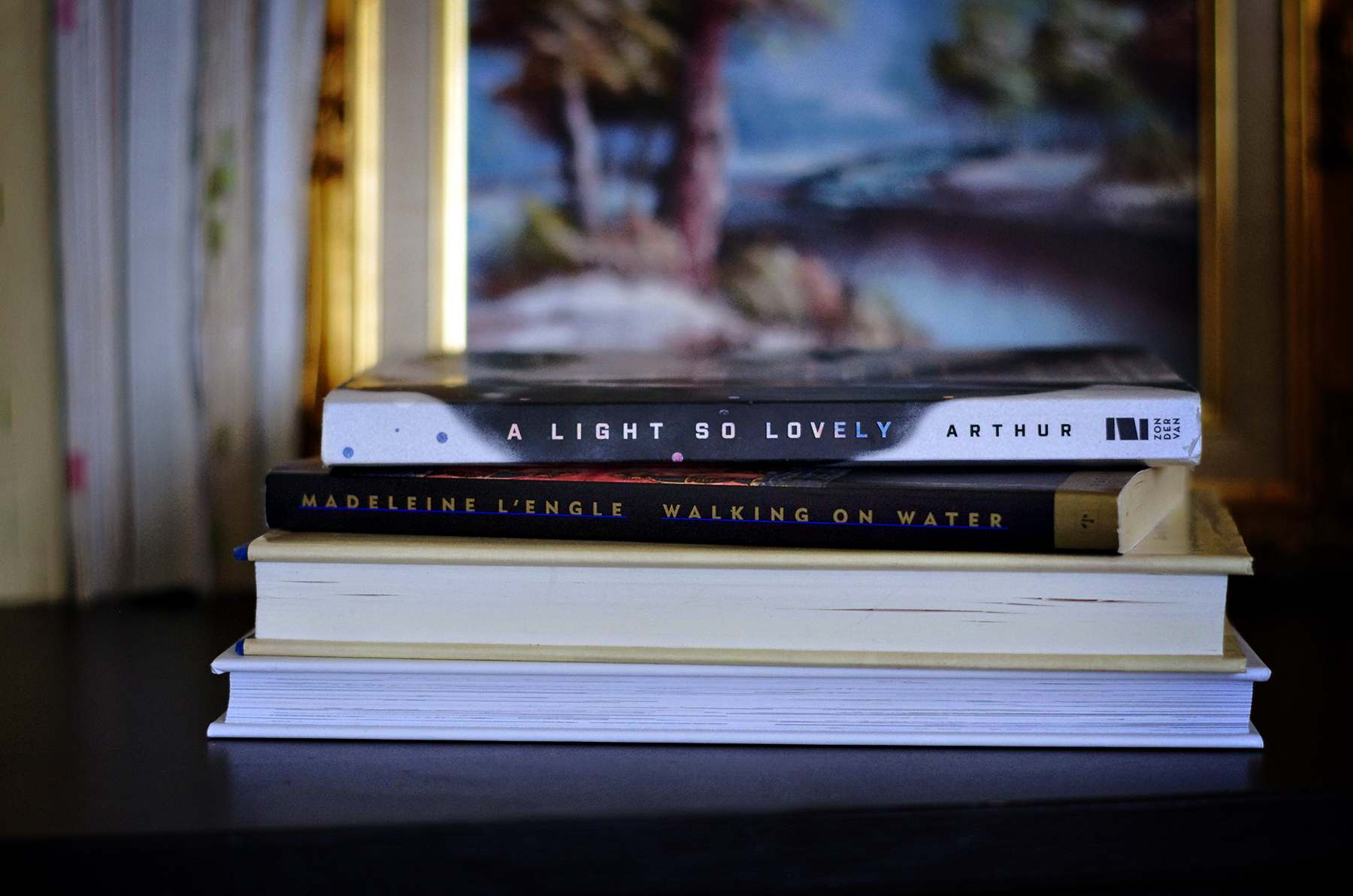

The first copy of Walking On Water, that I ever read was a borrowed copy from my local library. I’d only managed to read a few pages before I realized that checking out the book had been a mistake. With barely a chapter read, I had already copied down so many quotes into my commonplace book, that I knew that I’d need a copy of my own so that I could write in the margins, underline freely, dog-ear the pages and carry it around in my purse without racking up a heft of overdue book fees. Until that moment, I had never encountered anyone who spoke about faith and art and writing the way L’Engle did.

On every page of Walking on Water, I discovered a new vocabulary for the integration of art and faith.

I don’t know where exactly the idea came from, as I don’t remember anyone specifically declaring it so. Somewhere along the trajectory of my early faith journey, the sense that in order for a Christian to be an artist, their art must be about biblical things, wrapped its firm grip around me. I didn’t understand then why this belief was misguided, but I was wrestling and unsettled, which is why L’Engle’s Walking On Water became so important to me. She made room for curiosity, for questions, for reflection and listening. Through her own wrestling with what it meant to be a Christian Artist, L’Engle extended hospitality to those of us who were coming up behind her. She gave us permission to navigate the skeptical glances from onlookers who don’t understand how we might find it wholly acceptable to quote scripture, mystic poets, orthodox rabbis, atheistic scientists and Greek philosophers in the same breath.

L’Engle’s words for me, were both providentially timed and revelatory. At the heart of Walking On Water is the belief that our participation as artists is holy work not because of our qualifications, but because we are God’s offspring. She stressed this point when she wrote, “God is constantly creating, in us, through us, with us, and to co-create with God is our human calling”.[1]

She believed that good art, whether explicitly Christian in content or not, points to the Truth of Christ, because when a Christian artist serves the work, co-creating with Christ, the art inevitably reflects this union—this communion.

Her “expansive view of God’s love for all of creation”[2] opened my eyes to see art and writing in ways I had been taught not to. Throughout her book, L’Engle champions the value and necessity for engaging our imaginations. She clearly drew biblical parallels between God’s design of humanity—with minds capable of both rational thought and imaginative exploration, and contextual invitations found in Jesus’ own parables. His parables deliberately invite us to imagine and engage with the stories He told, figuratively and artistically.

L’Engle was the first person whom I ever heard declare that there is no distinction between the secular and the sacred.

Later, I discovered that the recently deceased, and much beloved pastor and author, Eugene Peterson, also shared her conviction on this.[3] Madeleine (and Peterson) came under fire from certain Christian groups for this belief.

Whatever your own convictions are on this matter, the very least that can be said of L’Engle’s writing, is that her work will provoke questions, which she welcomed. As woman who embraced curiosity and wonder, she said that more important than getting watertight answers, was learning to ask the right questions.[4]

I return regularly to her words, finding both encouragement and invitation in those well-worn pages. Ten years later, my own copy is now lovingly smudged and marked up with my own questions, in various colors of pen—evidence of my repeat engagement with her work—and with God, as I reconcile her thoughts with my own convictions.

This summer, when Sarah Arthur’s, A Light So Lovely: The Spiritual Legacy Of Madeleine L’Engle released, I jumped at the chance to have a review copy sent to me. And as it did with Walking On Water, Sarah’s book landed in my mailbox providentially the day before I left for a week at the beach with my family. Once again, I had the pleasure of unwrapping the gift of Madeleine’s work, only this time, with the generous help of Sarah’s gracious and thoughtful insight. And as it did with L’Engle’s book, my copy of A Light So Lovely, bares similar evidence of my engagement with the work.

What I love most about Sarah’s book is the honest way she offers more of Madeleine L’Engle’s story to us, born from interviews with friends and colleagues and readers who were all deeply impacted by L’Engle. A Light So Lovely includes stories of not only her high notes, but also the areas for which she came (and in some cases, continues to come) under fire, places of discrepancy and inconsistencies that remind us that L’Engle was no less human than the rest of us. Whatever discomfort some may find with L’Engle’s ideas about faith and art and science, Sarah writes, “Beyond Madeleine was the bigger reality of God’s presence in the world, God’s particular love for each one of us. That’s the light she wanted us to see.”[5] Madeleine believed that “to be truly Christian means to see Christ everywhere, to know him as all in all.” Sarah adds, “There is no sphere where God is not, and thus no place where God is incapable of transforming what evil has deformed.”[6]

A Light So Lovely graciously unpacks some of the false claims made against Madeleine for her embrace of science and faith, and for her sometimes manicured truths, about how real-life events unfolded, versus how she wrote about them in her books. Sarah generously reveals the depth of L’Engle’s faith and work as a writer, coupling some of L’Engle’s most moving and profound quotes with reflections from those who moved in her inner circle while she was alive.

I came away from A Light So Lovely with an even deeper appreciation for the legacy of literature L’Engle left behind, and an eagerness to once again, read through Walking On Water, with fresh eyes to see, and a heart to hear how God might answer the questions that arise as I read.

Madeleine L’Engle believed that her faith could stand up to questioning. Her writing reflects this same invitation for readers to bring all that we are before God with humble curiosity and wonder, to ask our questions, and to listen. And then to make our art.

[1] LEngle, Madeleine. Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art. New York: Convergent Books, 2016.

[2] Arthur, Sarah. A Light so Lovely: The Spiritual Legacy of Madeleine L’Engle, Author of A Wrinkle in Time. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2018.

[3] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fx_uJQ_e1YE

[4] Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art.

[5] A Light so Lovely: The Spiritual Legacy of Madeleine L’Engle Pg.11

[6] A Light so Lovely: The Spiritual Legacy of Madeleine L’Engle Pg. 55

As a sequin-wearing, homeschooling mother of four, Kris is passionate about Jesus, people and words. Her heart beats to share the glorious truth about life in Christ. She’s been known to take gratuitous pictures of her culinary creations, causing mouths to water all across Instagram. Serving as an advocate for Compassion International, Kris is Managing Editor of The Cultivating Table for Cultivating. She is the author of, Come, Lord Jesus: The Weight of Waiting and Holey, Wholly, Holy: A Lenten Journey of Refinement, and Everything is Yours. Kris is the founder and host of Refine {the retreat}. She writes at kriscamealy.com.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

Add a comment

0 Comments