Douglas Kaine McKelvey has been serving the body of Christ for decades through his written words and the craft of story. While he has written hundreds of songs during his career as a song writer, (many of which you have probably heard and loved without necessarily knowing who wrote them), the words you are most likely to associate with Douglas McKelvey are those in the books of every day liturgies found in Every Moment Holy, Volume I and Every Moment Holy, Volume II. These two volumes of prayers give words we can share in the common and help us find the holiness bound into the daily acts of our lives – the ordinary wonders of being human and being mortals meant for immortality. Words crafted with such piercing finesse as these and offered as prayer do not come without a cost: labour, discipline, obedience, and sacrifice. These good, holy words make a path for us to find our way into the throne room of The Lord when our own words have failed us. They are offered to us as acts of great love and humble service. Should the Lord tarry, these may well be the words pilgrim souls are reading and praying a hundred years or more from now as they search for the framing of prayer when their own words have fallen silent.

It is a great gift to have this conversation with Douglas discussing the labours and conditions of a writer’s life, the making of Every Moment Holy, Volume I and Every Moment Holy, Volume II, and to be given a glimpse into the processes that make such work possible.

Loaves, fishes, and small beginnings

LES: I love the story of how the first inkling of Every Moment Holy was sparked when you shared a liturgy that you had originally written to help center you before writing. You shared Liturgy for Fiction Writers with Andrew Peterson before a Hutchmoot conference. He loved it but then wanted liturgies for some other experiences like for beekeeping. In the course of creative acts that start bigger things in motions, there’s a little element of “If You Give a Mouse a Cookie…”, but there is also something else. Your story about the origins of Every Moment Holy captures something that I know to be undeniably true – the story of the loaves and fishes. In this enactment of the story, you offered a small thing that you had made to sustain yourself to share with others who might need it too. Perhaps it didn’t seem like much at the time. But in the offering of those loaves and fishes, without any expectation of it becoming something bigger, many others have been fed by what you have offered. Has it surprised you to see how it has grown? Do you also see instances of someone bringing what seems like a small offering to something and from that small beginning something much grows?

DKM: I’ve never been more aware—in an immediate, ongoing sense—of the story of the loaves and fishes than I was during the process of writing these two books. Volume 1 took about a year to write. Volume 2 took two years. And almost every time I sat down to write I was faced with the overwhelming sense that I was in over my head and utterly incapable of delivering anything that would serve the Body of Christ in any meaningful way, or of making these prayers what I desired them to be. I couldn’t escape that posture of forced humility, because I was so constantly and painfully faced with my own inadequacy and inability. All I could do was show up with the meagre bits I had to offer, which were usually just my time, and my attention, and my wavering willingness not to say no to the work before me on any given day.

So my only hope for these books to be helpful to other people, was the hope that this might be one of those good works that God had prepared in advance for me to do, and that if it was, then he would surely somehow bring it to completion.

I found a measure of courage in the possibility that God might take my inadequate offerings, and bless, break and multiply them unto the nourishing of many. Those were the specific words I prayed on many days as I wrote and rewrote and edited.

As I struggled to write and to shape these prayers, I identified so closely with that boy who showed up with his little pack lunch to hear Jesus, and then was asked to offer it to the Lord, that He might feed a crowd of thousands of hungry people.

While that sense of my own poverty drove me to my knees again and again, begging grace, begging that it would be God’s pleasure to somehow meet and multiply my insufficient offering by the mysterious workings of his Spirit, there was also a sort of freedom in it, because I knew that I couldn’t make of these books what I wanted them to be. It just wasn’t possible. So why feel pressure to do something I knew I couldn’t possibly accomplish? If there were going to be any lasting good that would come of any of these prayers, it would be because God had been pleased to enter the process and shape it toward his own ends—for the nurturing of His people and for his glory. So I labored in that hope, in the hope that indeed it might be His purpose to somehow use these labors.

So yes, the enthusiastic reception the first book had right out of the gate was a big surprise, and not something that I, or the publisher, had anticipated. For the first year we were just playing catch-up to try to get enough inventory to fulfill orders.

Living with the long view in mind

LES: When you launched into the original project of Every Moment Holy, I’ve read in an earlier interview that you only ever considered Rabbit Room Press for publishing it because you trust them to steward the project for “long-term service rather than short-term sales.” This reflects something you’ve called a “hundred-year vision”, making art that will outlast its creator for the benefit of those who will come later. How does this paradigm of taking a longer view change the way you approach your craft now? Does it change how you see the flow of time or the way you practice your daily living?

DKM: Most of my adult life I’ve been self-employed. Much of my time has been spent on speculative projects of one sort or another. Only a small percentage of such ventures ever came to fruition and yielded any sort of income, and even then, it often wasn’t enough to cover the bills. So at a certain point, as a father of three trying to provide for a family of five, I found myself investing more and more time chasing projects for the sole reason that I thought they had commercial viability. Often they were ventures other people invited me into, and often they were things I had zero passion for, other than the possibility that they might eliminate some of the perpetual financial stress my wife and I had over usually not knowing how we were going to pay bills the next week. But such pursuits almost never panned out. Or if they did, it was just a short reprieve.

After years of those sorts of pursuits, I reached a place where I was very burned out. I simply couldn’t write another song with the purpose of trying to create a commercial radio hit. I had chased so many projects that had little or nothing to do with anything I was passionate about, or with what I personally feel compelled to address and with whatever is unique about the voice I have to express such things with. I felt like I had lost my way, creatively.

Songwriting royalties had dried up as people quit buying music. The video work I was doing had dried up too, as the economy was in a downturn. I took a job doing cleaning and setup for my church. I started driving for Uber and Lyft. It was an emotionally difficult period of time. Here I was, in my late 40’s, and though I had encountered some sorts of brief “success” here and there over the years, none of it had stuck. None of it had “built” into anything sustaining.

It was during that time that I re-evaluated. And the questions I was asking myself were along the lines of “Okay, whether it yields any short-term financial benefits or not, what are the things I’m uniquely gifted to create? What does it mean to steward those talents? What sorts of artifacts do I want to leave behind me when this short life is over, in hopes that they might still speak to and serve people who will come after? And finally, What is my role in the body of Christ? What can I create that might offer meaningful service now to the communities I’m already a part of?”

I considered writers and poets who had lived even long before I was born, many of whom labored and died in relative obscurity, but whose works have inspired my wonder and shaped my thinking and my theology and I asked “Do I really believe in the realities of the Kingdom of God enough to embrace that unseen economy, to invest my time and energy in creating the sorts of things that I might be uniquely called and equipped to create, as a means of serving the body of Christ over time, regardless of whether those efforts meet with ‘success’ during my lifetime, and regardless of whether my circumstances require that I continue to drive tipsy revelers around Nashville in the wee hours of the morning?”

So yes, that shift in my perspective toward vocation, stewardship, and service to community does also involve a shift in how I conceptualize the flow of time. I see more clearly now that I’m only a very small part of a story that began long before me and will continue long after me. I’m one small part of a body—the church universal—that extends across history past, present, and future, and, recognizing that, I want to be faithful to fulfill the function assigned to me in the times appointed for me. I want to perceive more clearly and consistently how this moment touches on eternity, that I might be more invested in those things that are eternal.

Crafted to endure

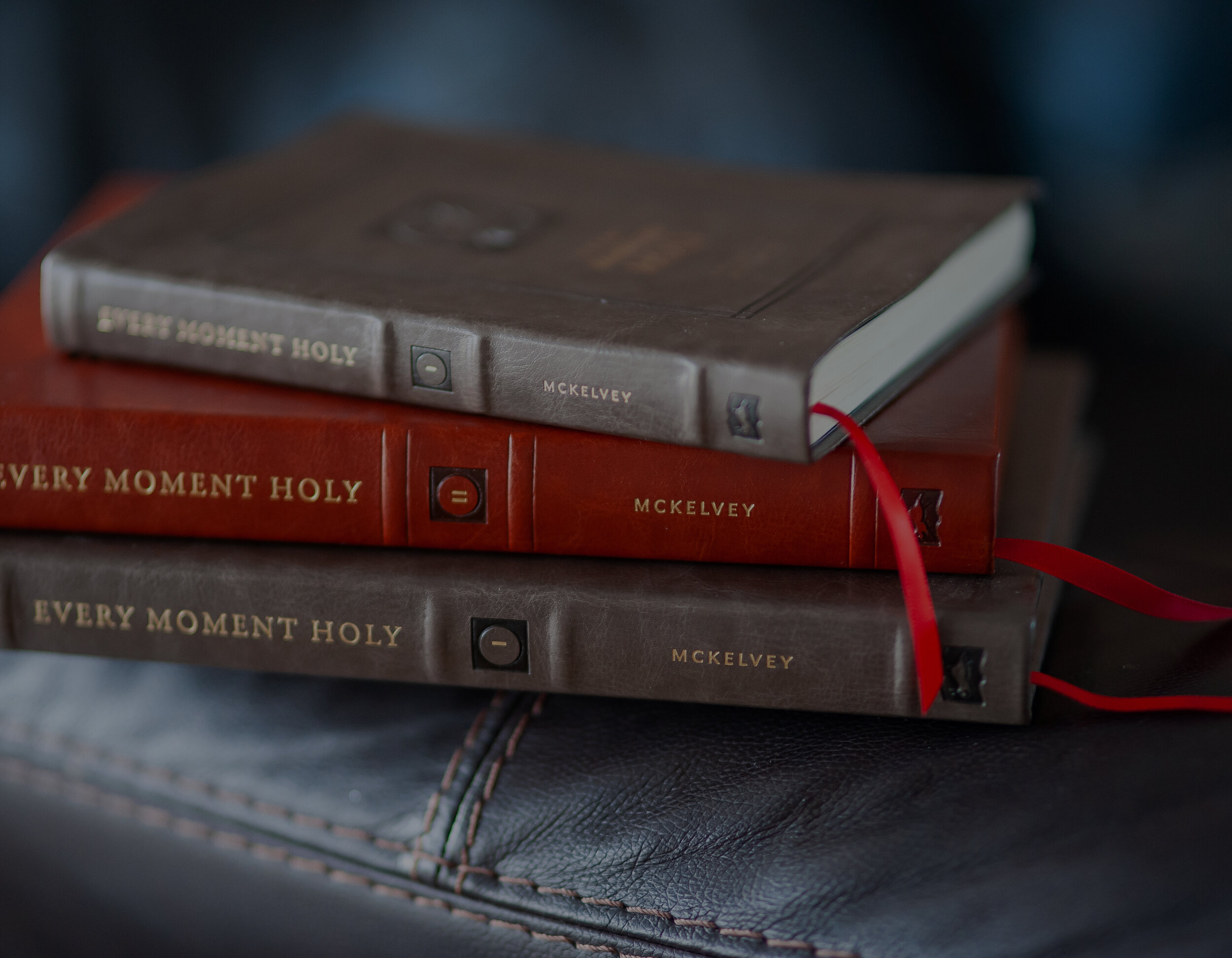

LES: The book design for both volumes of Every Moment Holy by Rabbit Room Press is distinctive in its feel of craftsmanship and layout. It is such a pleasure to hold and to read. From its very first printing it has always felt like a beautiful book for its word content but also as an artifact crafted to last. Everything from the paper selections and gilded edges, the fonts and interior design, to the artwork by Ned Bustard, to the leather binding and ribbon bookmark capture a particular tension between something that is at home with the old and yet comfortable with the new. It is a remarkably harmonious book in its physical creation. Did you have a role in the design process, or did you give the manuscript to Rabbit Room and trust them to give form to it? Who selected the Scriptures used in the sidebars?

DKM: The physical beauty of these books was something I had very little to do with. I was the beneficiary of other people’s excellent choices, and that’s something I’m very grateful for. Pete Peterson and the folks at Rabbit Room Press took the lead on all of that and implemented their vision for what the books could be aesthetically. Ned Bustard, the illustrator, also played an important role in design and layout. I was invited to weigh in with my opinion on some of those elements, but I wasn’t responsible for the decisions. When I saw what Rabbit Room had done with the physical design, it was simply one more confirmation that I had made the right choice in taking the project to them.

A theology and a practice of dying

LES: Within the space a few paragraphs in in the forward to Every Moment Holy Volume II You mention two very significant phrases. One is “the practice of dying by degrees” and the other is “theology of dying”. How do you define your theology of dying? How do you see these the elements of theology and practice working together? Are there ways you would suggest that we might more intentionally practice dying by degrees?

DKM: As I worked on the new book, one of my evolving hopes for Volume 2 was that it might serve somehow as a catalyst for conversations about these very questions. Before I began writing these prayers, I hadn’t much considered a theology of dying and whether we in the modern, western church even have one that is very robust or scripturally-informed. (I single out the church in the west, as I expect that the Body of Christ in some parts of the world might—because of greater proximity to death in their daily experience—have a more well-formed theology in that regard.)

But as I read through a stack of books about death, dying, and grief (some written by pastors and theologians) I began to notice a repeated assertion: We as a culture have insulated ourselves from those who are dying, and therefore from proximity to death, to the point that even in our churches the subject is most often only addressed in a funeral sermon.

But it wasn’t that long ago that pastors considered as one of their primary responsibilities the ongoing preparation of their congregations for their inevitable deaths. It was more frequently preached about than it is today. After all, it’s knowledge of our own mortality and of the uncertainty of our days that can serve to open us to the convicting and sanctifying work of the Holy Spirit, and to point us toward amendment of life, better stewardship, and eternal hope. So there’s that very basic, practical sense in which we need to be regularly reminded of our own mortality, that we might live more fully as citizens of the eternal kingdom.

But there are other cascading effects of becoming comfortable with a life lived in view of our deaths. One of those is that we can then become a community that does a better job of grieving with those who grieve, of sharing their tears, and serving in small and helpful ways, rather than maintaining a distance because the situation seems awkward, and we don’t know what to say or what not to say. Obviously, there are people who do a great and sensitive service in these areas already, but I’m looking at the big picture. Most of us feel a sense of awkwardness and inadequacy at the thought of shepherding another through their dying. And we’ve also lost the notion—once common in the church—of dying well, of intending to navigate that final season of our own lives in such a way that those who witness it will find eternal hope and encouragement. This used to be a “thing” in the church. And it was part of what pastors intentionally prepared people for throughout their lives, that even in their dying they might bear witness to God’s goodness, grace and glory, by holding to his promises and looking forward to the glory to come.

Finally, there’s the sense of what dying really signifies for the believer. Maybe “signifies” is to weak word, because I don’t think it’s only metaphorical. It’s much more than that. Scripture tells us that when we are baptized into Christ we are baptized into his death. Then we are told that if we would follow Jesus from that point we must take up our cross daily. That cross is the instrument of our own death. We are to die to our selves, to our own corrupted and selfish desires, to our dreams of lesser things, to our own ambitions and definitions of success. Day by day we are to be dying to those things, slowly releasing all that we yet cling to or aspire to, that we might continue to follow our Lord along the path where he leads us.

The moment of our physical dying, then, is but one more step on that disciple’s journey that we’ve been on from the start. It is part of that journey. It is the point at which—willingly or unwillingly—we finally must release all remaining vestiges of our own impoverished hopes, and claims, and power, and possessions, leaving them in a useless pile on the near shore, as we wade across that river where life is swallowed in life, and we at last see face to face and embrace the One who is the sum total of all our deepest longings, the One for whose sake we have all along been learning to die day-by-day.

I think these are essential truths for which we, as individuals and as the Body of Christ, ought to cultivate a deeper understanding and awareness. The beautiful thing is that—while we might have long shied away from ongoing consideration of death and mortality—for the believer it is not ultimately a dour, morose and depressing reality. It is actually the pressing knowledge that over time re-forms a shaky faith into a thing that is diamond-hard, beautiful and brilliant, and sparkling with eternal hopes that cannot be shaken.

Death is an unnatural enemy and an intruder in God’s good creation, and it will one day be destroyed. Praise be to God! But in this mortal life, it does serve a function. It reminds us that we are not gods. That our time is short. That our choices matter.

Structure and a place of safety

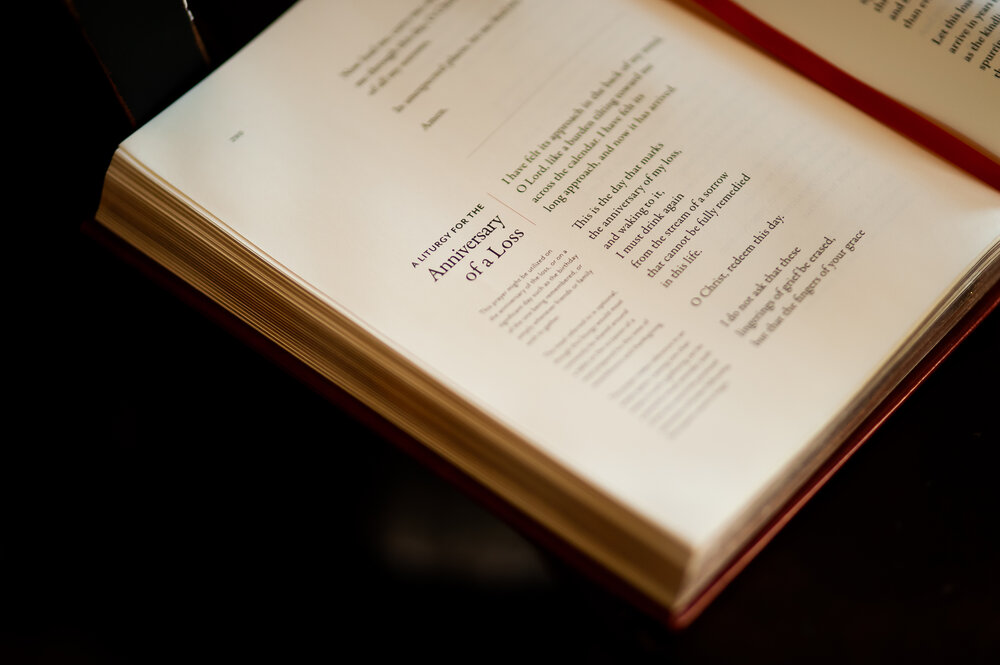

LES: There is a change in this Volume besides the thematic elements. More of these liturgies are structured to be read alone as well as with others. This gives the volume of prayers a very personal feel, and private. Because of that it has a quality of safety and safety is a precious commodity for the grieving. Because this volume has that quality, it invites readers into it from Christian traditions who may not be familiar with liturgy and with more formal worship approaches. Would you explain why the book is ordered the way it is? Invocation, Seasons of Dying, Interlude, Seasons of Grieving, Benediction?

DKM: I didn’t set out with an agenda to write a greater number of one-person prayers for Volume 2, but I think your perception is valid. Whether these are prayers that a person navigating their own season of dying might employ, or ones for caregivers, or for those who grieve, there are so many facets of those topics that are inevitably going to be worked through in a more internal way. So the result is that there are more prayers here that are personal outpourings of the heart to God than there are ones that are divided up for corporate use. Of course, it’s still easy enough to divide those up if multiple people want to pray through them together, or, conversely, for an individual to pray through ones that are laid out for a group.

Thematically, it made a lot of sense to arrange the book with the first half being prayers for the season of dying, and the second half being prayers for seasons of grief. The invocation, interlude, and benediction take their places before, between, and after those two major sections. The invocation is a prayer that was important for me personally to express early on in the writing process, as a kind of thesis statement of the subjects I would be exploring as I wrote.

The interlude, “A Liturgy of Intercession Against the Kingdom of Death,” was one of the longer prayers I had written and then realized it didn’t fit neatly into either of the two major sections. But it did seem to sit right at the intersection of the two, as it acknowledges our desperate situation as a people living in the shadow of death and suffering from its works, and then turns in supplication to the only one who can deliver us from this long bondage.

The benediction was one of the last prayers I wrote, but one that I knew all along I would write. Volume 1 explores a wide cross-section of daily life and struggle and celebration and closes with “A Liturgy of Praise to the King of Creation,” a prayer of praise to the Lord of life who is sovereign over all of time and matter and life. Volume 2 explores mortality and life lived in the valley of the shadow of death. It needed to close with “A Liturgy of Praise to Christ Who Conquered Death,” a summation of the theme that death will not have the final word, that Jesus has already defeated it by his death and resurrection, and that a day will come when death is no more. In order to be true, the book had to end with that affirmation, and I think I personally needed to write that one at the end of two years spent considering death and grief.

Guides along the way

LES: Being a man of letters and deeply at home with books and music, are there books or music that have particularly helped you in the formation of a better theology of death? Any that have particularly comforted you?

DKM: I read a number of topically-related books as I wrote these prayers, and none impacted me more deeply than Nicholas Wolterstorff’s poetic account of his own loss and grief, Lament for a Son. That book actually allowed me to recognize and name as grief, a burden that I had long been carrying.

Another book that was broadly helpful as I thought through some of these topics was Matthew McCullough’s Remember Death.

There are many songs that can help prepare my head and heart to enter a space where I can write about sorrow, grief, and hope. Drew Miller’s Desolation and Consolation EP’s were fitting in that regard. As was Andrew Peterson’s Resurrection Letters, Vol 1.

When I’m actually writing though, if I have music playing it has to be instrumental and unobtrusive, though it also needs to have a strong emotional undercurrent. I frequently wrote to instrumental pieces by Zöe Keating, Nils Frahm, Ludovico Einaudi, and the “soundtrack” to my children’s book “The Wishes of the Fish King” that my own daughter Ella Mine composed and recorded several years ago.

Shepherd and pastor, writer and scribe

LES: Writers have a variety of roles and sometimes in the life of a writer those roles change. The changing of role is often a sign of life and a sign of maturity, where one might have started out writing on less difficult subjects but find they are led to a different kind of writer’s calling. The work that you have done in both these volumes is as much like the work of a shepherd and pastor as it is a writer and scribe. What has prepared you to craft words on such holy ground? How do you write about such difficult realities, listen to and curate so many stories of heart break, without being crushed by the weight of it? Even a bone deep belief in the resurrection of the body and promised reunion in the new creation, does not spare the heart from aching in the face of separation now. How do you hold on to any hope, and keep any kind of perspective in the midst of such work?

DKM: If someone had asked me what I’d most like to be writing during the last two years, I probably would have answered “A fantasy novel.” I find all writing to be labor-intensive, but there’s an element of escape (or at least the temporary illusion of it) in chasing a fictional story.

But that would only be a partially true answer, because I couldn’t have escaped the sense that I ought to be about the crafting of prayers for the dying and the grieving during that season. I believed it was the work I should be investing in, and because of that I wouldn’t have found much peace by avoiding it to chase something else.

I’m so often a reluctant follower whose first response is like the son in Jesus’ parable who tells his father “No, I won’t go work in the field,” but after wrestling with his own reasons for not wanting to do it, eventually he gives a heavy sigh and heads to the field where he sort of knew all along he was going to end up anyway once he had dealt with his own selfish desires.

I can really relate to that son. When there’s something in the way, it usually turns out to be me.

My relationship to my writing work in general is always complicated and often chaotic. I wrestle through it in fits and starts. I sometimes hide from it for days. I experience it as a joy and as a burden. I feel utterly inadequate to the task, even as I feel inevitably drawn to it. Add to all of that the gravity of the subject matter of this particular book, and of the personal experiences of loss and grief that people were sharing with me throughout the process, and it was a recipe for a very non-linear season of work. There was never a consistent, productive routine. Each day was its own struggle.

The ironic thing is, at certain points there can be a sort of encouragement even in that. The seemingly impenetrable resistance to what one sets out to do becomes a sort of “inverse clue” that one might actually be on the right path. I’ve lived long enough to notice that any protracted attempt to serve the kingdom of God is going to be met with resistance, internal and external. So when you encounter that, in the moments you can have a moment of objectivity enough to name it as such, you can take heart in the knowledge that from the enemy’s perspective, what you’re doing might in some way be worth resisting.

And if it’s worth resisting (from the enemy’s perspective), then it’s probably worth doing from an eternal perspective.

At the same time, I know that I’m utterly unequipped to fight that sort of battle on my own, so it also takes me back to the awareness of my own need, poverty, and dependence on the One who alone can bring to completion in and around and through me, whatever good works he has called me to.

Even so, my tendency through most of the process is just to want to escape from the struggle and the insecurities it brings to the surface. That’s my first instinct and impulse—just to run away from the stress and the pressure.

Because of that, for the first year-and-a-half of writing, there was always some mental carrot I was dangling in front of myself, and it was usually something like “I bet I can finish writing the rest of these prayers in eight weeks or so, and then I can move on to something fun.” And I really believed in the plausibility of those scenarios, even the seventh time I was telling myself and my publisher something like that and then pushing the publication deadline back yet again.

But the subject matter of the book continued to expand as I met and conversed with more grieving people, read more accounts, and pushed deeper into the subject matter. The topic of grief is “bigger on the inside.” As you try to move through it, it fractalizes into more and more facets and nuances. So anytime I would think I was nearing the end of the writing process, the subject matter would once again outgrow the boundaries I had set, and I would again recalibrate and say “Okay, but another month-and-a-half should be enough.”

Eventually I reached a day where I had a little epiphany and realized that in order to serve the prayers themselves—and through the prayers to hopefully serve the people who might one day use them—I simply had to stop writing toward any imagined deadline. Trying to write to a deadline was putting me at great risk of signing off on drafts prematurely, just so I could move a prayer to the “finished” pile, even though I might not be confident it was what it needed to be yet. I finally realized that all faithfulness required of me was that I do the particular task before me each day—writing, re-writing, editing—until each of the prayers had become as near what they ought to be as I could craft them, and until all of the topics I felt compelled to write about had been covered.

So there was this distinct moment of surrender to the process, about three quarters of the way through, in which I realized I was following a forest path I couldn’t see the end of, and all I could try to do was to show up each day and be faithful to craft however much I could, as best I could, in those few hours. I was learning something of what it means to pray for daily bread, and to trust that what is needed will be given. The prayers would be completed when they were completed, when there was nothing that still nagged at me about their content or aesthetic, and no red flags that anyone else reading them and giving feedback was raising. I couldn’t speed up the process or force the project to completion.

As far as I can tell, our role in the advancement of Christ’s kingdom consists mostly of not saying “No.” Or of, after initially saying no, reconsidering and showing up and saying “Your will be done.” It seems to be God’s good pleasure to work through weak and inglorious and insecure people.

If we feel drawn to a work that we know we have no business doing, and that we lack the internal and external resources to complete, we’re being called to a place of humility and dependence where our own neediness is going to be exposed. And that’s a good thing, but not an easy thing. And it’s not an enjoyable thing. And yet, it can produce abiding joy.

One other reason that I’m drawn again and again to the “holy ground” where sorrow and hope intersect, is that I have little patience for any belief that cannot bear the full weight of my experience, or of human experience more broadly. We live in a world where horrific, unspeakable things have happened, and are happening, and will happen. And each of us will be touched by pain and loss and suffering somewhere along the way. Will we truly be met and held in those deepest, darkest places? The answer matters. Is our Creator with us even in the midst of those experiences? Does our faith rest on something real? Will all of this loss be redeemed? These are the fundamental questions.

And the act of writing is often my personal process of wrestling through those questions. There is a way in which I am willing to plunge into those experiences, because I know that if I chase God, and find that yes, He is there, even in the very heart of the worst that this world, and my own brokenness, and the enemy of my soul can do, then I can so easily trust He is also there in all other moments of life.

On the other hand, if it turned out that He were absent from our suffering, then it would mean that the connection I feel to Him through experiences of wonder, awe, beauty, and delight was all a lie, or at best, irrelevant.

So I feel compelled, in my writing, to hunt the Holy Spirit in those hardest places where to find Him is to find Him in all places and for all time.

And in my experience, it has always been in the hard places when I asked the hard questions, fearing that there would be no satisfactory answer, that the answer I have been given is God’s presence, in which the other, lesser questions I had been asking ceased to be relevant, and I realized that this was all I truly sought and longed for—to be held in the limitless love of the One who made me.

Making a way through

LES: Douglas, before you wrote either volume of Every Moment Holy, you spent years crafting hundreds of song lyrics. You also wrote other books. In that particular wisdom of God’s economy, He never wastes our pain or training. Do you see a correlation between those years of writing lyrics to what surely had to be an unlooked for calling to write liturgies for our common life? How did writing song lyrics prepare you for this labour? How did God prepare Lise for your work in these two volumes?

DKM: From a craft standpoint, the fifteen years I spent as a song lyricist were essential. As was the time spent learning screenwriting. And the attempts at poetry writing I’ve made here and there. Each of those disciplines requires a writer to learn to communicate much, in very small amounts of real estate. Complex things must be pared down to what is essential, and to combinations of words that evoke much more than they might actually state. Lyric writing and poetry made me sensitive to the rhythm and cadence of words as well.

So yes, in hindsight I can see how necessary those parts of my path were, to prepare me for the writing of liturgical prayers now. But, of course, none of that was my own design. I have never seen much further than the step I am currently taking. And if I thought I saw further and tried to predict and plan how things might go, my assumptions inevitably turned out wrong. I was mostly just giving a shot at the next thing that seemed to present itself. And then, all of a sudden, it all adds up to what I’m doing now.

Keeping company and kinship

LES: Ned Bustard illustrated both Volume I and Volume II. What was it like working together over an extended time? What did working with him facilitate in you to make your work in this possible? Did working with the same person change the way you approached the project?

DKM: There’s a long and winding backstory that Ned and I share, which I wrote about a few years back here: https://rabbitroom.com/2018/11/intersecting-lines/. Suffice it to say, that when Ned came on board in 2017 to illustrate Vol 1, we were mutually unaware of our past history together.

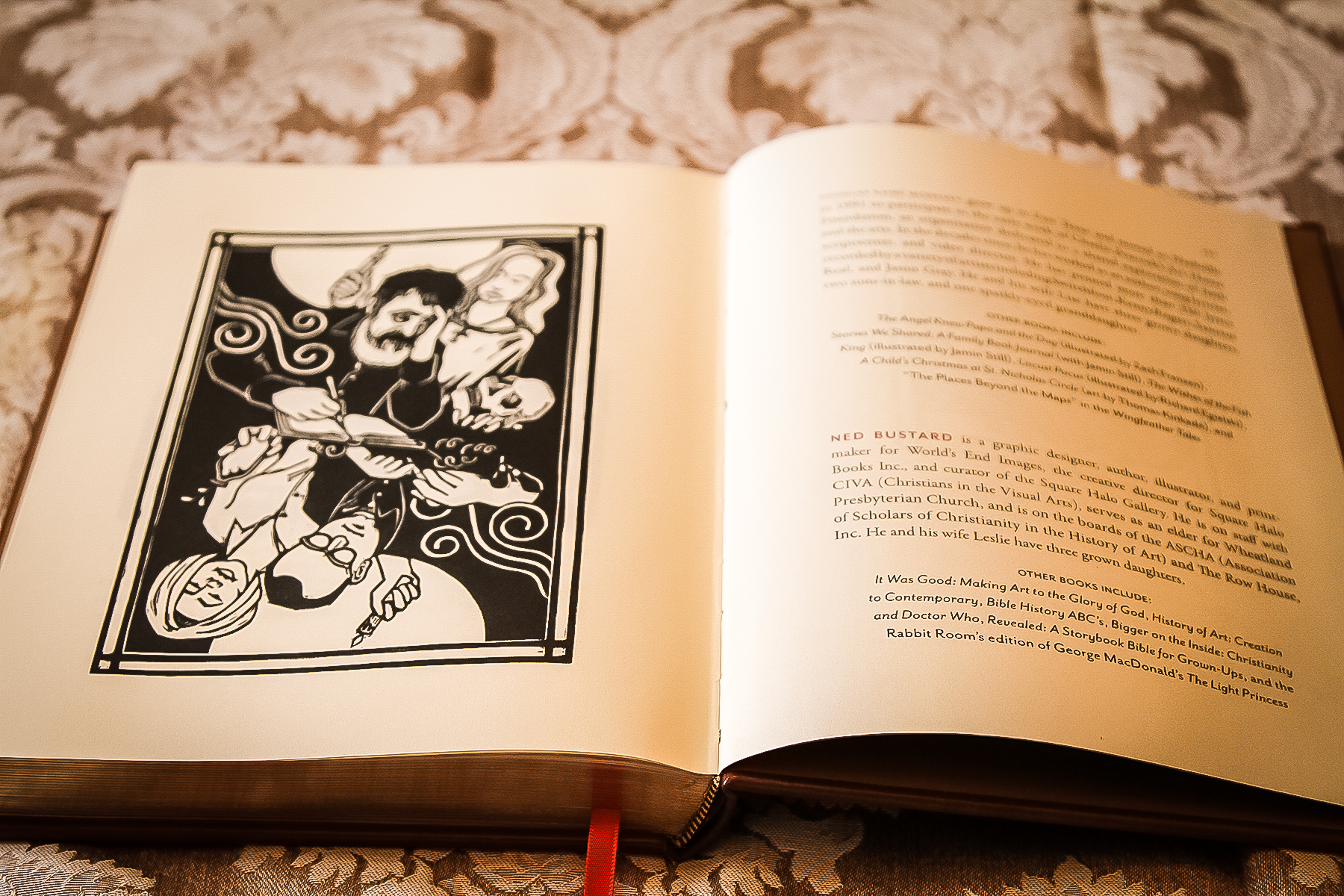

Ned’s linocut style of old-world symbolism (with bits of modern whimsy thrown in for good measure) was a perfect fit for the aesthetic of the book though, so I was absolutely delighted to get to work with him. He has a deep knowledge of the history of Christian symbolism in art, so I could suggest that a particular illustration include symbology to communicate a particular idea, and Ned could, off the top of his head, give me four or six choices that the church had historically used to convey that idea.

We spent a lot of time considering together and sorting through which of the prayers it made most sense to illustrate, and then we would have a lot of back-and-forth where Ned was creating mock-ups for me to respond to with any changes or additions. In some cases what you see in the books is just the realization of Ned’s brilliant initial draft, and in other cases they reflect several rounds of tweaking and shaping, or even of starting over from the ground up.

As with any creative collaboration, we had to learn how to marry our particular strengths and to find a place where our artistic visions intersected and overlapped. I’ve had collaborative projects in the past where that was a struggle, but for Ned and me it was never a problem. We were able to mesh our aesthetic sensibilities from the start.

In addition to his artistic skill and wealth of knowledge, Ned is also very humble and unassuming, so he’s a really easy person to become friends with. And he’s not self-promoting, so part of the fun of getting to know him is that you only gradually become aware of his long list of accomplishments and accolades. In that regard, Ned Bustard is a man of mystery and of many, ongoing surprises.

Illustration (c) Ned Bustard for Every Moment Holy, Volume II. Image by Lancia E. Smith for Cultivating.

Those who stand watch over a labouring writer

LES: Douglas, near the very end of the volume there is a portrait of you and Ned as joint labourers for this work. The image of each of you is immediately recognizable. It is haunting to me. Behind you is your wife Lise holding a candle, and behind Ned is Leslie holding a candle. So much is said in this image. Would you share about the role that your wife played in the making of this collection? What is the role of one who stands guard during creative labour, and who prays over the workman and the work?

DKM: Lise has, in many ways, been the one who carved out the months-long spaces in which I write. She has tended so many of the details of daily life and family so that I can tussle with words and thoughts and ideas. I work most efficiently when I can focus on one thing. The more numerous the necessary details of life vying for my attention, the more likely I am to become paralyzed in terms of making any progress on my work. I will go all day without eating sometimes, if left to my own devices, because it’s just too much of an interruption to consider going downstairs and having to think about and make choices about what food to eat. Pathetic, right? But it’s true. I need a buffer, and so often the many tasks involved in providing that buffer fall on Lise.

I probably don’t thank her enough.

Scratch the word probably. I don’t thank her enough.

That illustration was one Ned and I were in cahoots on, as we wanted to acknowledge that our labors aren’t pursued in a vacuum, and that there is work others are doing to make possible the work we’re doing, even though those more anonymous labors aren’t obvious on the finished pages of the book. Leslie and Lise are the ones doing most of that heavy lifting in our lives, so the illustration was intended as a tribute and a thank you to them.

Different times, different experiences

LES: While there is obviously a great deal of similarity between these two books together, you were writing them under different conditions to meet different needs. What do you see as significant differences besides theme in the two writing experiences?

DKM: The obvious difference, as you mentioned, is theme. Volume 1 is topically broad and Volume 2 is topically focused. The difference in the writing experiences though, has a lot to do with where my life was in those writing seasons.

Vol 1 was written during a very chaotic year. Most of the video work I had been doing had dried up, and I was leaning heavily on credit (in general I don’t recommend this…) to buy the time to write the book, so I was feeling the financial stress of seeing my debt grow pretty rapidly. My youngest daughter was starting college that fall. My two older daughters were both getting married that summer. So there was massive life transition going on, and the stresses you would expect with those sorts of things, and also stresses we didn’t expect.

On top of all that—if I’m not being too candid here—it just felt like nothing was working in my life. Relationships seemed either distant or difficult. As a family we were all dealing with a long-term medical trauma that had left us disoriented. There was grief I was carrying that I hadn’t yet been able to name, let alone work through at all.

So that whole year was just a chaotic mess.

And somehow, by God’s grace, the book was written in the midst of all that.

As soon as the book was completed, everything changed. I would go so far as to say everything changed almost immediately. All the stressors went away. Relationships that had seemed strained and distant for months were easy and buoyant again. The first printing of the book sold out within a couple weeks of release, which meant that for the first time in years my wife and I didn’t have to be worried about how we would pay our bills in the months that followed.

So the experience of writing Volume 1 was one of great chaos and stress on many fronts followed by immediate relief at the end of the process.

Not so with Volume 2. During those two years of writing, I wasn’t living under the same stresses and pressures. It was not a visibly chaotic season. But there was a steady accumulation of weight. There was a great gravity to the subject matter. Reading so many chronicles of loss, and having so many conversations with grieving people, does not leave one unchanged—and it should not leave one unchanged. It takes a different kind of toll, and leaves its marks. But it’s also a good and right thing. It’s the kind of weight we’re called to bear with one another. It’s part of the process of beginning to learn what it might mean to enter the grief of another and to mourn with those who mourn. And I’ve got an awful lot to learn in those regards.

So with Volume 2 there was this gradually increasing burden, but it felt holy and fitting. And when I finished the writing process, it didn’t go away. Whatever weight had accumulated didn’t just evaporate. There was no “bounce-back to normal.”

So the ways in which the writing left a mark was very different with the two volumes, and the residual effect has been very different so far as well.

Thank you for asking. It was probably a good exercise for me to have to think through and articulate all of that.

A storied ending

LES: Many of us here at Cultivating, and certainly within the circles of the Rabbit Room, are very familiar with the concept of The Great Story, and with the profound promise that “the stories are true”. However, not all of us understand the significance of having a storied ending for ourselves. Could you explain a little more about what it is to have a storied ending and why it changes what our lives mean?

DKM: As I understand it, there was a time in western culture when the church was more serious about the business of “dying well,” of being conscious of the fact that the season of one’s dying was very much to be an expected part of one’s following of Jesus, and an event that one would do well to prepare for throughout one’s life rather than just trying to make sense of it in the moment when it’s happening.

Christians consciously desired that the way they died, the way they traversed that valley of the shadow, would be a witness and a source of great encouragement to their fellow believers. They saw their own dying as part of their ministry to the Body of Christ.

And if one is to do that in a way that isn’t just the fruit of some misguided stoicism, or a thin attempt to “put on a good face,” then one must have already become, over time, strongly oriented to the hope of Jesus’ resurrection, and the promise of our own.

We find true courage to face our own mortality, and true hope in the vision of a new heaven and a remade earth, not typically in one sudden moment at the end, but by an incremental, lifelong process of steadily relinquishing our own ambitions and desires, and investing in the promises of Christ instead.

And it’s the willingness to remember death, to remember throughout our lives how brief and fragile our lives are, and how certain they are to end in death, that allows us to work backward from that inevitable moment, and to say, in light of that coming moment when my mortal body will breathe its last, how ought I to live today? What would I choose in this moment? What would I cherish? What would I spend my limited time and energy and resources in pursuit of?

Or better yet, we might phrase the question as “When I reach the end of my short span of days, what greater Story do I want to see that the smaller story of my own life had become a part of?”

I believe there are no better stories than the one about the High King who will return for His bride, to dwell with her forever in the unspeakable splendor and inexhaustible wonder of the heaven and earth He has created for their shared and perpetual delight.

The featured images of Douglas McKelvey are (c) of Lancia E. Smith and used with her permission for Cultivating and The Cultivating Project.

Jonathan Rogers hosts one of our favourite podcasts ~ The Habit Podcast. I highly commend his interview with Douglas McKelvey.

Lancia E. Smith is an author, photographer, business owner, and publisher. She is the founder and publisher of Cultivating Oaks Press, LLC, and the Executive Director of The Cultivating Project, the fellowship who create content for Cultivating Magazine. She has been honoured to serve in executive management, church leadership, school boards, and Art & Faith organizations over 35 years.

Now empty nesters, Lancia & her husband Peter make their home in the Black Forest of Colorado, keeping company with 200 Ponderosa Pine trees, a herd of mule deer, an ever expanding library, and two beautiful black cats. Lancia loves land reclamation, website and print design, beautiful typography, road trips, being read aloud to by Peter, and cherishes the works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and George MacDonald. She lives with daily wonder of the mercies of the Triune God and constant gratitude for the beloved company of Cultivators.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

Lancia and Doug, thank you for this interview. There are too many little phrases and moments to point out, but a lot of things I need to hear right now. A lot of things that make me feel less alone and hopeful. Thank you.

Matthew, you are most welcome. Douglas has given us a very generous interview and I am with you in feeling less alone and more hopeful from reading through his replies!

So very rich. Oh, that we would live our lives with such vision and purpose. So much to identify with in this. Thank you for sharing!