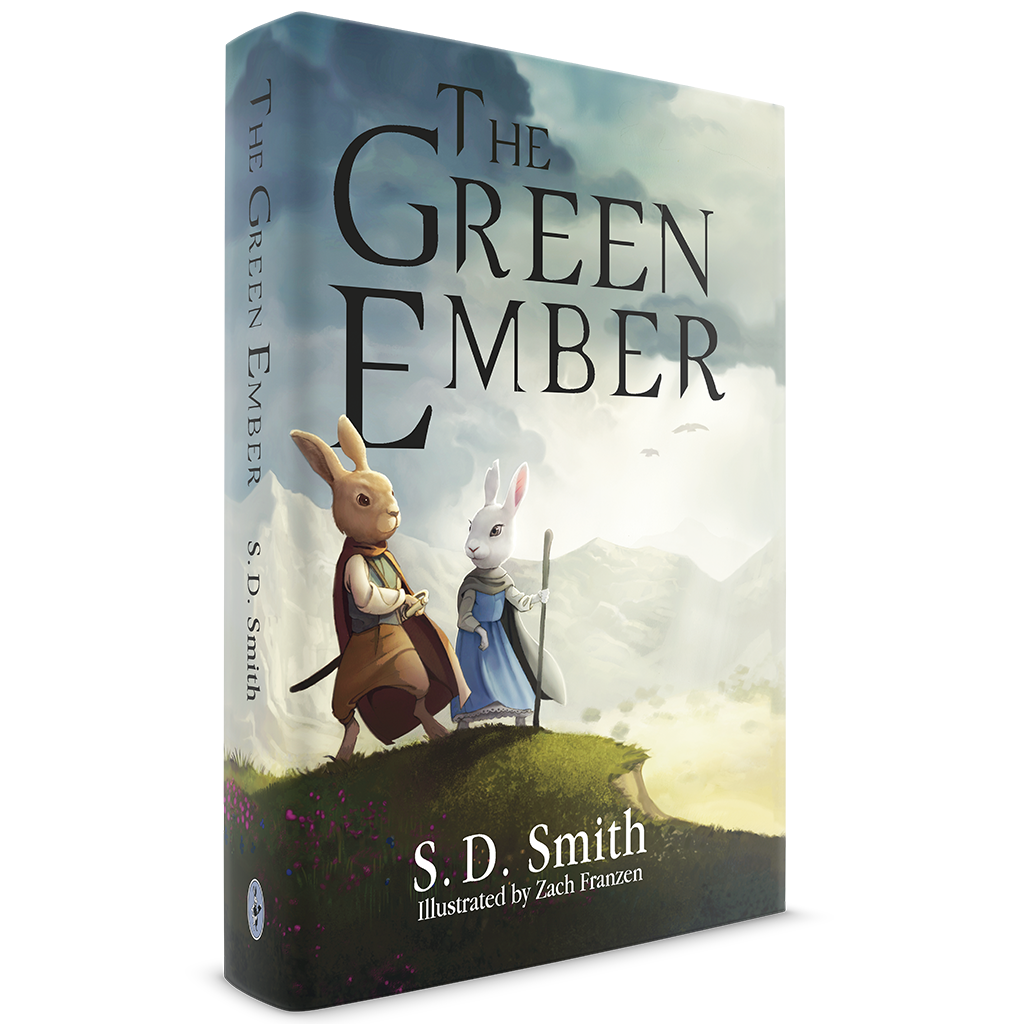

S.D. Smith is the author of the extraordinary Green Ember series, a marvelous unfolding of glorious tales of rabbits with swords and hearts of warriors. The Green Ember tales have reached hundreds of thousands of readers of children who love them along with their parents and grand parents, too. Exactly as Sam describes them, these are “new stories for old souls.” Rich in adventure, honest in addressing hardship and pain, stirring in character formation, the Green Ember series is like taking a good, long drink from the river of virtue and a baptized imagination. Personally, I have loved this series from its first publicly shared Kickstarter campaign in 2014, and confess I’ve cried every time I’ve read these words aloud (as my granddaughters can attest):

“My place beside you, my blood for yours. Till the Green Ember rises, or the end of the world.”

A superb wordsmith, I also know Sam to be kind, patient, patently funny, and deeply generous. He embodies the courage that is new in the hour of our times while rooted in what is old and true. It is my honour to interview Sam here and my joy to share it with you.

Sam, thank you for your kindness and generosity in doing this interview for Cultivating. It is such an honour to have this time with you.

Calling and keeping it simple

LES: There is something so deeply true and familiar in the stories of The Green Ember, something that has often felt to me as a truth being called into existence by the Creator both through the writing of them, and through the reading of them. What has calling looked like in your life as a writer, husband, father, friend…? Have you felt called by this particular story world? How has that calling changed you in your answering it?

SDS: Like so many vocations, this one began very modestly. The Green Ember started off as stories I told my kids. What has happened since is more and more families are enjoying it. I try to think of it in those simple terms. I have seen God answer many prayers, and one of them has been that he is changing me in this process. He’s using the experience of serving and loving the audience I have to grow and show me more of his love for me. I am grateful and glad about that. But it’s still a pretty small calling, in a sense. And I say that as someone who appreciates and advises thinking (in a sense) very small.

LES: One of the things I’ve loved in your writing is the piece you wrote some years ago about the purpose of the Story Warren. You said,

“This is what stories can do and be in the mind of a child. Children (and all of us) are suited to receive stories and for those stories to inform the imaginative life. How many of us have read a book, or seen a movie, and afterwards burned to do what we have experienced? (And we really have experienced it.) We want to be as bold as Luke Skywalker (without all the whining). We want to be as faithful as Samwise Gamgee, as pure in heart as Lucy Pevensie. Well, children don’t just aspire to great characters in the aftermath of stories, they inhabit them. They walk away and become what they love.

So, if they indeed become what they love, how important it is that what they inhabit is full of virtue. It is of utmost importance that we are not asleep at the tollbooth on this little avenue of imagination, this person-defining road to our children’s affections.” ~ S.D. Smith, Why Story Warren

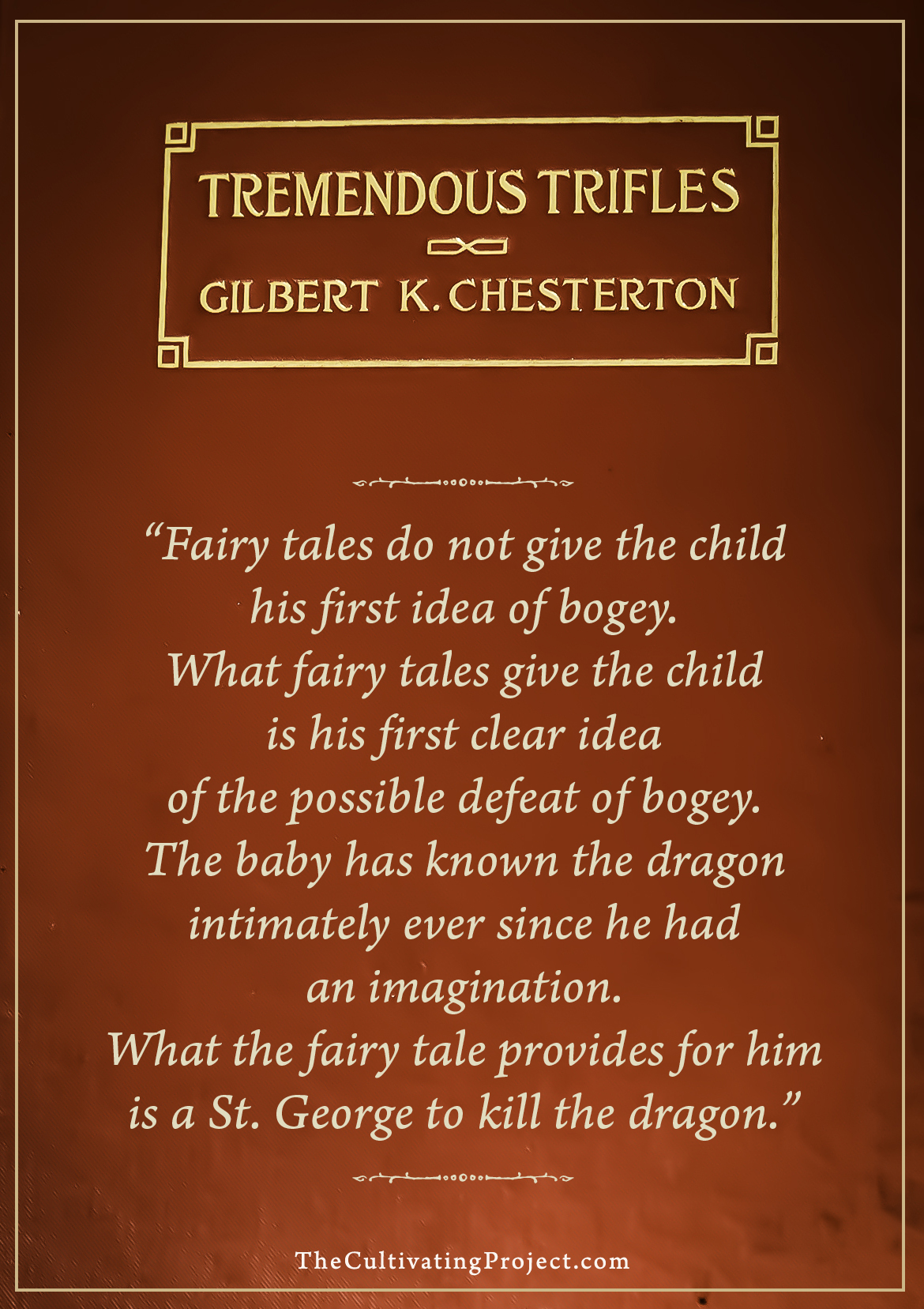

That is a powerful conclusion to come to about children inhabiting the great characters, not just aspire to be them. That concept echoes Jesus saying, “Dwell in Me and I will dwell in you.” (John 14.4-5) It also echoes both G. K. Chesterton and C. S. Lewis about children needing to be introduced to heroic figures in literature to give them models for courage and virtue as they face dragons to slay. How did you come to that understanding about inhabiting the great characters? How has that understanding shaped the way you tell stories?

SDS: I have to keep my focus as simple as possible. There are times when I am reflecting on the power and importance of stories, and the words of Chesterton and Lewis are on my lips and in my heart, but usually I am just writing stories for kids I love. And the stories come from a garden I can’t take credit for cultivating. Or, I can’t think about the garden so much at that time. Or the sun. Or the rain. I can only think about the meal I’m making at the moment and the people I love who will eat it. So it’s all there, in the garden, but my main vocation now is making meals. I’m more of a storyteller than a story expert, if that makes sense. I have to keep my eyes on the job at hand.

LES: This phrase gives me chills still every time I read it, and my granddaughters can tell you that I cry every time I read it out loud to them.

“My place beside you, my blood for yours, till the Green Ember rises, or the end of the world.”

How did this come to you as you wrote the story?

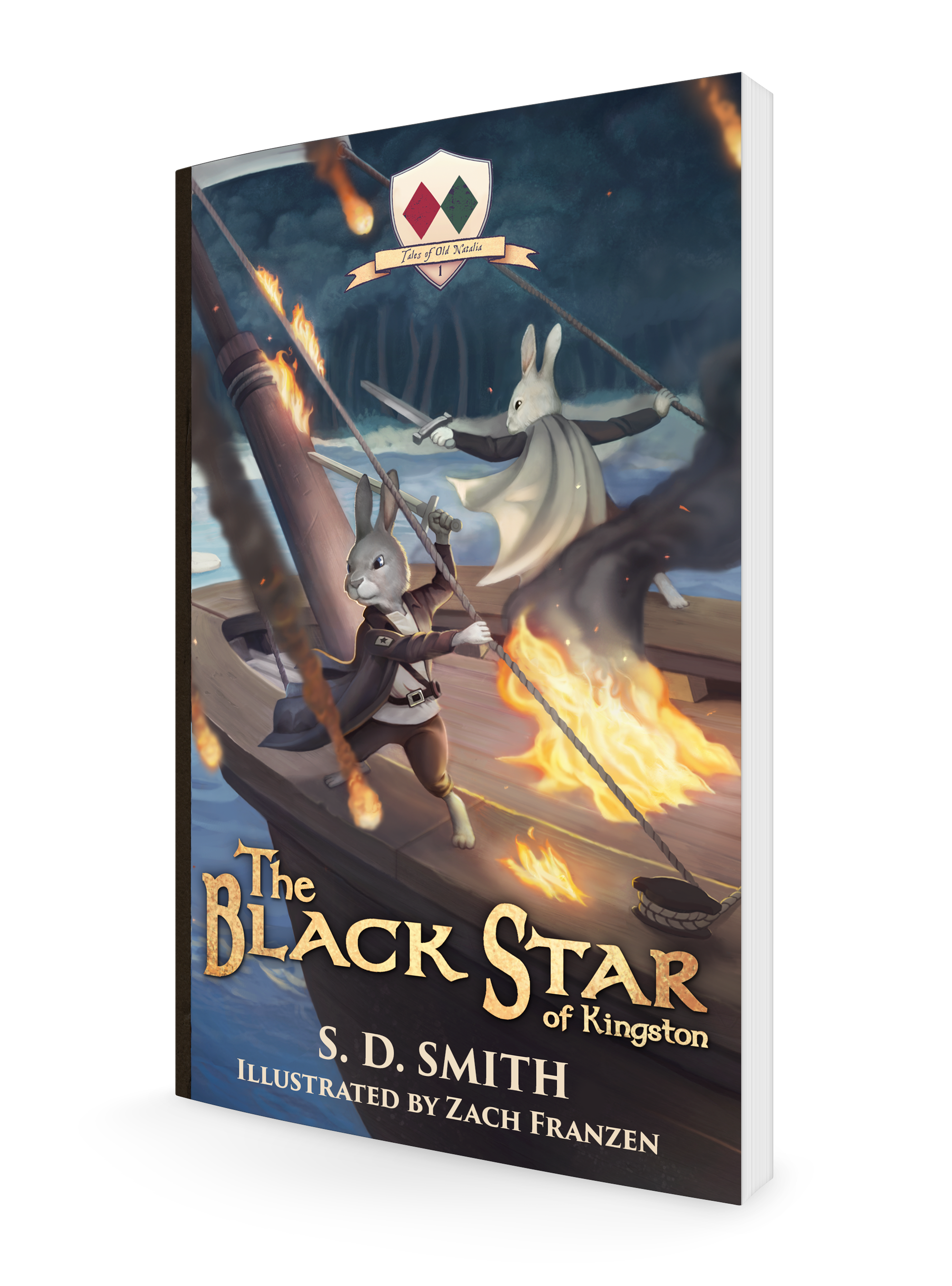

SDS: I don’t really know. It was there, in the air, and it was important. It came right out, as I recall, in a scene where a character was appealing to a shared history, a code, a love and loyalty, to show another character (who was troubled and failing) they were both on the same side. I didn’t know everything about it when I first wrote it. I later wrote a little book (The Black Star of Kingston) to find out where it came from and why it mattered so much to the characters.

A shed of his own

A shed of his own

LES: A fascinating commonality among many writers is having a writing shed or hut – separate from their house – where they do their dedicated writing. Virginia Woolf called it “a room of one’s own.” Malcolm Guite has his Temple of Peace. Andrew Peterson has his Chapter House. Neil Gaiman has his writing sheds. And you have The Forge. How does your writing shed function for you in your writing and how did it come by this name?

SDS: A guy named Chris Yokel suggested the name. It fits, since I’m a Smith and that’s where I work. I forge stories in this tiny garden shed converted for my purposes. I love it, honestly. It’s mostly free of distraction, useful, simple, and appropriate for my vocation. It’s not grand or spectacular in any way. It’s a good place to work.

Sneaking past watchful dragons of resistance

LES: C. S. Lewis wrote about how certain kinds of literature could bypass our reasoned defensiveness and smuggle truth into us without our being aware of it. The phrase he used is, “sneaking past watchful dragons.” Many of us now use that phrase when we describe getting around a resistance of some kind so we might accomplish something beneficial. As writers and artists, we are all too familiar with ‘resistance’, and the worst source of it often seems to be our own self. And then there is the experience of resistance through spiritual oppression outside of us, a spiritual attack which requires a response of real spiritual warfare. Do you also experience ‘resistance’ as a writer? If so, how do you get past yourself in order to write? How do you do deal with the oppressive elements if those come to bear on you?

SDS: This would take a very long time to answer with full honesty, but I will say that modest habits practiced with some consistency are great weapons against resistance. Everything is easier than writing. Writing a book is a fool’s adventure. It can’t possibly work. So do it scared, stupid, and show up for it every day. At some point the “resistance” gets less insistent when good habits grind it down over time. I know of no other way. Here are two quotations for our arsenals.

“We first make our habits, then our habits make us.” John Dryden

“You can’t wait for inspiration, you have to go after it with a club.” Jack London

LES: Assuming, Sam, that you are like most of us who have to practice our craft and work at growing our skill sets, how do you practice your craft as a writer in order to improve? Are there other people you study or work with, writers you look at to learn from; other storytellers who inspire you to want to learn your craft better?

SDS: I tend to agree with those who say most writing books are distractions from the real work and the real learning and growing. My heroes are probably Jane Austen, Arthur Conan Doyle, Charles Dickens, P. G. Wodehouse, Patrick O’Brian, Louisa May Alcott, and Lewis and Tolkien, of course. I do work to improve my craft, mostly by reading and writing and being interested in more than reading and writing. Painting will make you a better writer. Poetry certainly will. So will soccer, skateboarding, stump grinding, and gardening—if we pay attention. I have a sneaking suspicion that much of what passes for education in writing are programs for failed writers to learn from failed writers how to be failed writers.

It might sound (or be) cynical, but whatever helps us hide from the real work of writing is our enemy. You don’t need permission to begin, to grow, or to succeed. You don’t have to be Dickens or whomever is hip now. Most of us can be good writers. Few will be great. You have to be the best version of you as a writer you can be right now. That means writing now. Write now. And then keep growing, as a human, and as writer.

Beginning and becoming

LES: I’ve heard you mention that you lived in Africa for a time when you were growing up. How did that experience define how you see yourself and others? Has that shaped your approach to the way you tell stories?

SDS: I love Africa. It’s still in me. It’s a part of that garden that formed and fed who I have become and am becoming. There’s some of mix of Appalachian and African in me—an Afrolachian concoction—that shapes me and my work in ways I can’t identify easily, but see glimpses of from time to time. Every writer has these. They often feel like bugs, but are really features.

LES: One of the verses I have returned to again and again over the years is Hebrews 12.11. It has come to mean much more to me as I have gotten older and matured in Christ than when I was just starting out and really didn’t understand it.

“Now all discipline seems painful at the moment—not joyful. But later it yields the peaceful fruit of righteousness to those who have been trained by it.” (Tree of Life Version)

In The Passion Translation it reads,

“Now all discipline seems to be more pain than pleasure at the time, yet later it will produce a transformation of character, bringing a harvest of righteousness and peace to those who yield to it.”

As a gardener I know full well that when I am training plants it sometimes involves pruning, and always involves the plant being asked to do something that is not easy or “natural” for it, but what I am requiring results in greater fruitfulness and greater health and greater effect in the garden overall. I have never found the training of the Lord easy or natural either, but I have found Him trustworthy in His discipling of me – often through hardship, illness, or extended loss. That long disciplining has produced a very different character in me than I would have had if left to my “natural” tendencies, and it has produced changed characters in those closest to me who have shared that process.

How has that disciplining (training) from the Lord shaped you? Has He been faithful in ways that you can at least partially see and understand? Are you able to trust Him that He is working for your certain good?

SDS: I am so grateful (now) for my many failures, for the many times my hopes have been thwarted. For the ways I didn’t succeed at the wrong times. I get asked pretty often how I produced The Green Ember Series by writers who want to imitate my process and produce something similar. But none of them really want that. I don’t want that for them. Because it’s a story of intense pain. They need their own pain and their own journey, not to imitate mine. I bless God and praise his name for loving me as his child and for leading me on this painful, productive, amazing journey.

I don’t think anything valuable comes into the world without labor and pain. Not a baby. Not a book.

It’s not good to be alone

LES: Much of what I see of you online and in social media is in context of relationships. Not surprisingly, your storytelling and characters are also rooted in relationships and in community. How have your core relationships – wife Gina, kiddos, brother Josiah, and your extended family, influenced your creative work, and shaped who you are?

SDS: Much in every way. The theoretical truth of us being made for each other, that our lives make sense only in relationship to other lives has become more obvious and realized for me over the years on many fronts. I see more now, as I get older, how different gifts fit together for the glory of God and the growth of a community. My stories teem with these themes, not because of an intent to teach, but a reflection of that Reality of which we are all a part. We need one another. It’s not good for man to be alone. It’s not good for Sam to be alone.

LES: None of us pursue high risk & creative work without intertwining that risk others, especially those we love. There is always a cost to what we do whether in obedience or in disobedience. How has your writing of Green Ember shaped and impacted your family? Does you being faithful to your calling serve them in ways that are different that you expected?

SDS: It’s a dangerous thing, heading out your side door and walking ten feet to the Forge. Dangerous for everyone that you’re not going to a “real, safe, reliable” job. I think it has been a big opportunity for growth in our family and has allowed our kids to experience the goodness and provision of God in unexpected ways. In ways you can’t experience unless you’re vulnerable. I think they may see more possibilities—at a young age—than I did on some creative and entrepreneurial fronts.

Cultivating Courage

LES: Courage is the core virtue and value that we focus on through Cultivating and The Cultivating Project. Courage to face life bravely enough to create beauty through whatever our artistic crafts may be, to work good in the circle of our own life, and to tell truth as beautifully as we are able no matter how weary or afraid we are, or how dark the world is becoming. Courage is the center core and call of Green Ember. I love your video leading up to Green Ember’s finale and the simple line: “Stories to make us brave.” What is your sense of why the Lord has you writing about courage more than say kindness, courtesy, long-suffering… or any of the other important virtues?

SDS: I don’t know. Maybe because I need it. Because I am afraid and anxious often. Again, these stories are very, very local to me. Very close to home and heart. I need stories to make me brave. I read them. I write them. Maybe the Lord is giving some good gifts to kids who will face things they need courage for. I don’t know the big picture, but I know I need courage and I need to know more than that I ought to have courage. I need stories to make me want to be courageous.

Endings Matter

LES: In Ember’s End, the entire Green Ember series comes to a real finale. Why end the story here, and why does it matter that you do?

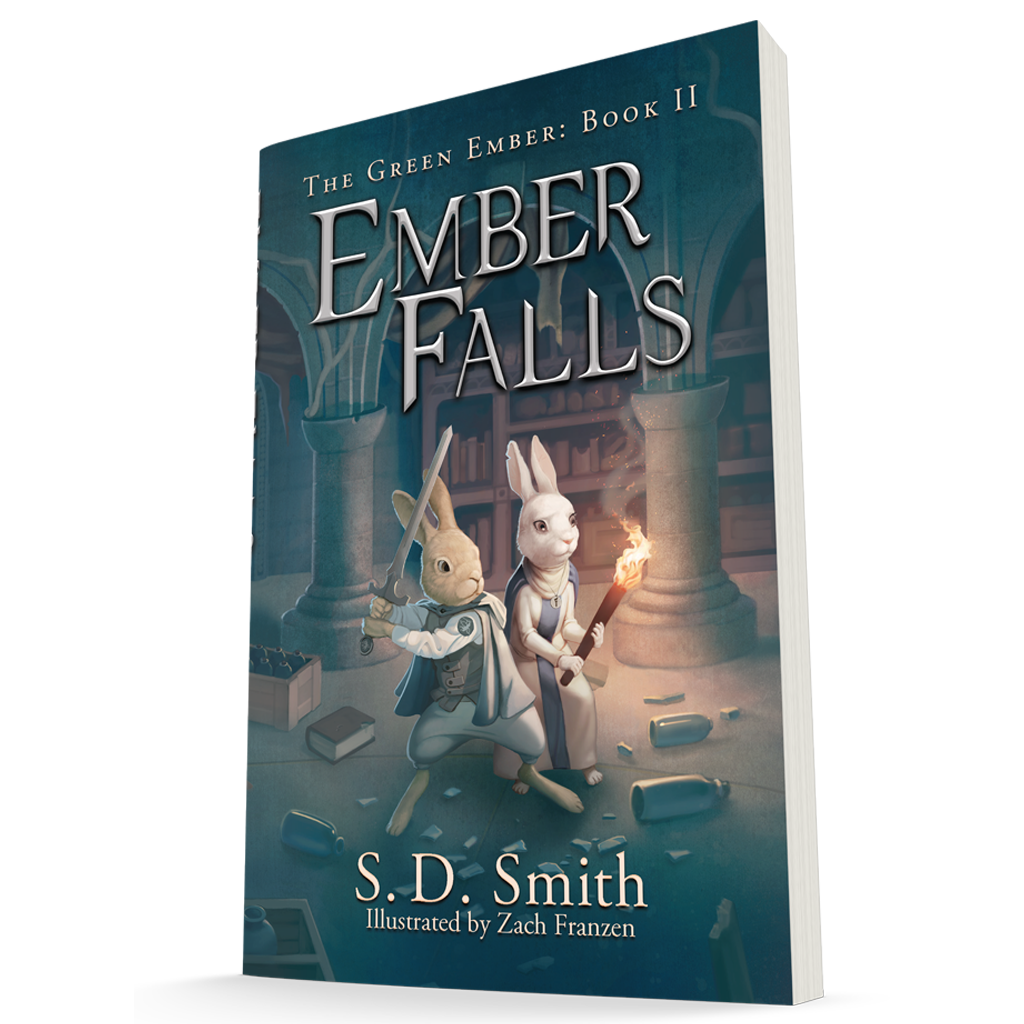

SDS: Bilbo Baggins said, “Books ought to have good endings.” I never wanted to just extend the main series unnaturally to accommodate more sales or anything like that. I have been praying I’d be alive and well enough to finish the story I began in The Green Ember and I’m so grateful I was given that gift. I’ll write more books in the Green Ember world (I’m writing one now) if I’m able, but it was important to me to end Picket and Heather’s story as well as I could.

The featured images of S.D. Smith are courtesy of Lancia E. Smith and used with her permission for Cultivating and The Cultivating Project.

Lancia E. Smith is an author, photographer, business owner, and publisher. She is the founder and publisher of Cultivating Oaks Press, LLC, and the Executive Director of The Cultivating Project, the fellowship who create content for Cultivating Magazine. She has been honoured to serve in executive management, church leadership, school boards, and Art & Faith organizations over 35 years.

Now empty nesters, Lancia & her husband Peter make their home in the Black Forest of Colorado, keeping company with 200 Ponderosa Pine trees, a herd of mule deer, an ever expanding library, and two beautiful black cats. Lancia loves land reclamation, website and print design, beautiful typography, road trips, being read aloud to by Peter, and cherishes the works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and George MacDonald. She lives with daily wonder of the mercies of the Triune God and constant gratitude for the beloved company of Cultivators.

Leave a Reply

A Field Guide to Cultivating ~ Essentials to Cultivating a Whole Life, Rooted in Christ, and Flourishing in Fellowship

Enjoy our gift to you as our Welcome to Cultivating! Discover the purpose of The Cultivating Project, and how you might find a "What, you too?" experience here with this fellowship of makers!

Yes yes yes!

Everything is easier than writing.” I’m so encouraged that I’m not the only one that feels this way!

“You have to be the best version of you as a writer you can be right now. That means writing now.” So much wise advice in this interview. I love what he says about being grateful for failures and hopes thwarted, for “not succeeding at the wrong time.” What a world of trust and perspective is wrapped up in that phrase.

“Writing a book is a fool’s adventure. It can’t possibly work. So do it scared, stupid, and show up for it every day.” That sounds like advice not just for writing, but for every good thing in life.